Tomorrow, when the Biden administration releases the details of its proposed budget, one thing will be clear. At over $750 billion for spending on the Pentagon and related work like nuclear warhead development at the Department of Energy, the budget will be far in excess of what’s needed to defend the United States and its allies, especially at a time when the most urgent challenges we face, from pandemics to climate change, are not military in nature.

It bears repeating just how high current Pentagon spending levels are by historical standards – far higher than at the peaks of the Korean or Vietnam wars or the Reagan buildup of the 1980s; over three times what China spends; and over ten times what Russia spends. And that’s not even counting expenditures by U.S. allies. There is ample room to reduce the department’s budget while making the country safer.

One area of particular concern is the Pentagon’s plan to build a new generation of nuclear-armed bombers, missiles, and submarines, along with nuclear warheads. Just this week the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) put the price tag for this plan at $634 billion over the next ten years, a 28% increase over the last time it made such an estimate. While some of the increase is a result of ramping up production on key systems, much of it is not – tens of billions of dollars of the increase stem from expected cost overruns, a near certainty in weapons programs of this size and scope. This is far too high a price to pay for weapons that are both dangerous and unnecessary.

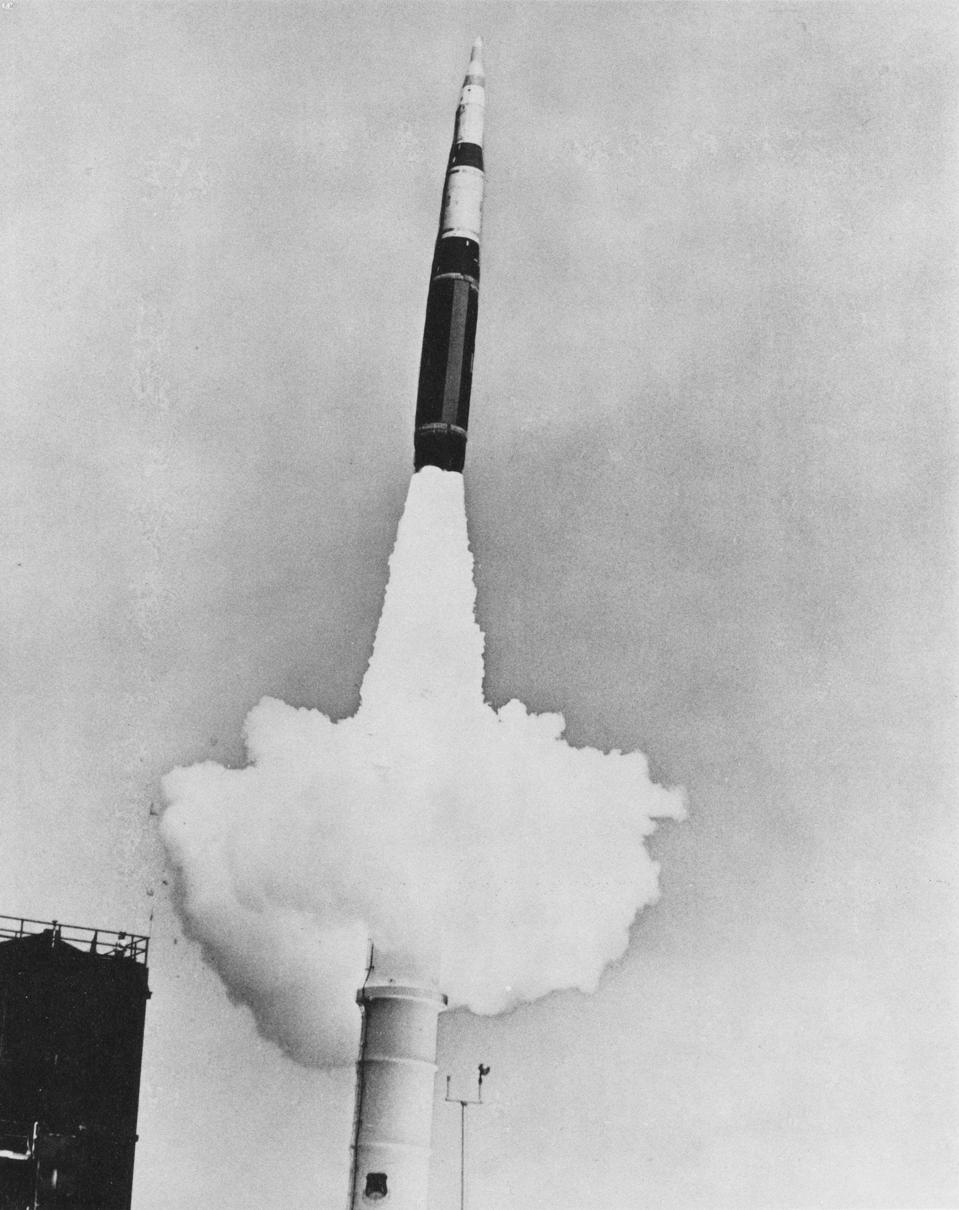

View of a Boeing LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBM missile as it is launched, 1970s. (Photo by USAF/Interim ... [+]

A case in point is the Pentagon’s new Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), known by the Pentagon as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), and by its detractors as the “money pit missile.” As former defense secretary William Perry has noted, ICBMs are “some of the most dangerous weapons in the world” because the president would have only a matter of minutes to decide whether to launch them on warning of an attack, greatly increasing the risks of an accidental nuclear war based on a false alarm. This risk is completely unnecessary. As the organization Global Zero has demonstrated in its alternative nuclear posture review, a force comprised of ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-armed bombers would be more than sufficient to deter any nation from attacking the United States, with ample firepower in reserve. Not only is a new ICBM not needed, but it will make America and the world less safe.

Given all of the above, the new ICBM – which is slated to cost at least $264 billion over its lifetime – should be cancelled to free up funds for more urgent national priorities. If the Biden budget includes funding for the missile, Congress should eliminate it, as called for in legislation sponsored by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA). Their bill would take any funds allocated for a new ICBM and invest them in developing a universal coronavirus vaccine and doing research on how to prevent future pandemics. At a minimum, the program should be paused while an independent study of alternatives is conducted.

A second element of the Pentagon’s nuclear modernization plan that cries out to be cancelled is the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile, a new nuclear weapon proposed during the Trump years. Not only is the system redundant given all the other ways the U.S. has to deliver nuclear weapons, but, like the new ICBM, it could increase the risk of an accidental nuclear conflict, as Kingston Reif and Monica Montgomery have explained:

“Mixing conventional and nuclear cruise missiles would . . . decrease the value of the conventional missiles – as any launch of a conventional missile would inherently send a nuclear signal – and increase the potential for unintended nuclear use in a conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary – since the adversary would have no way of knowing if the missile was nuclear or conventional.”

As Reif and Montgomery rightly note with respect to the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile, “The weapon would be a redundant and dangerous multi-billion-dollar mistake.” As such, the system should have no place in the budget of an administration that has pledged to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. defense policy.

As presidents from John F. Kennedy to Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama have noted, the ultimate goal must be to eliminate nuclear weapons altogether, as called for in the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which entered into force earlier this year. None of the major nuclear weapons states have signed up to the agreement, but they should, and the sooner the better. In the meantime, it’s important to reduce the risks of a nuclear conflict. Forgoing weapons like the new ICBM and the nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile will do just that. If the Biden administration doesn’t eliminate them in its new budget, it should reconsider them in the course of its upcoming review of the U.S. nuclear posture.