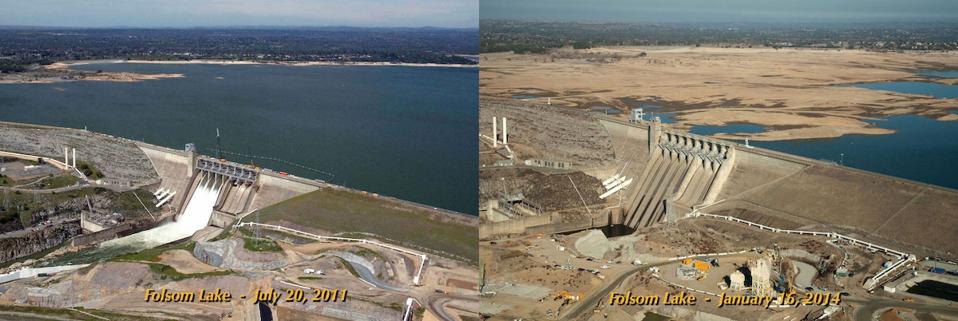

Blackouts and megadroughts are threatening the western U.S. Shown here is Fulsom Lake, a reservoir ... [+]

The western United States, from Washington down and around to New Mexico, is facing the largest risks of blackouts in history. California was bad enough last year.

As Malik, Baker and Chediak discuss in Bloomberg Green, “The specter of blackouts highlights a paradox of the clean-energy transition: Extreme weather fueled by climate change is exposing cracks in society’s move away from fossil fuels, even as that shift is supposed to rein in the worst of global warming.”

“States shuttering coal and gas-fired power plants simply aren’t replacing them fast enough to keep pace with the vagaries of an unstable climate, and the region’s existing power infrastructure is woefully vulnerable to wildfires (which threaten transmission lines), drought (which saps once-abundant hydropower resources) and heat waves (which play havoc with demand).”

It’s even worse as California and other states shut nuclear plants, replacing them with gas. Or hopes and dreams. Shuttering coal plants has meant most of these states have to import electricity from their neighbors, a temporary move that only makes matters worse because the amount available to export dwindles as those neighbors have less and less to give. Presently, no western region generates enough electricity to meet high periods of demand, and all rely on imports to avoid blackouts.

So what happens when all these states experience droughts, wildfires and record heat at the same time? Like what will probably happen this year?

Bad things will happen.

Of course, everyone is assuming bad things will happen this year and already electricity prices are soaring, up three or four times what they were last year, as we anticipate the shortages that will likely occur. Except in regulated markets like much of Washington State.

California is probably in the worst place. It’s in the second year of their most recent drought. Much of the state’s reservoir storage is only at half normal, dangerously low as they enter another serious wild fire season.

Northern California has received not even half the average historic precipitation for this time of year and, so far, this is the 3rd driest water year on record. And there isn’t likely to be any more precipitation of significance until the fall. So hydropower will dry up somewhat as well.

Statewide snowpack is about 30% of average for this date. Temperatures have been warmer than average, and warmer temperatures increase evaporation and dries out soil much more quickly, further reducing streamflows, groundwater recharge, and stressing already-dry forests and aquatic ecosystems.

The major Sacramento Valley reservoirs are all quite low. Shasta, Oroville, Folsom, and New Bullards Bar are all lower today than they were on this date in any year of the 2012-2016 drought. This is disturbing since Shasta ran out of cold water early in 2014 and 2015, killing about 95% winter run juveniles. The present drought appears to be even worse.

Agriculture is where this will hit hardest as it uses so much more water and has so little in reserve. Throughout the 2012-2016 drought, 70% of California’s irrigation groundwater was lost to over-allocation of the state’s groundwater resources, plummeting the state into a domino effect of consequences that still plagues the state today.

From job losses by the thousands, skyrocketing crop prices and long-term environmental and socioeconomic impacts, the devastating toll droughts unleashed on Californians and the rest of the West highlight the need for increased water resilience efforts. And serious planning.

There are some things we can do, but planning is critical. Relatively new companies, like the public benefit corporation AQUAOSO Technologies with their Water Security Platform, aggregate thousands of data sets to identify the scale of water risks and decide how best to address them. Accurately analyzing water risk, providing insight on water stress across the American West, and giving a more comprehensive view of environmental data allows better decision making.

Even at the financial end where this understanding plays into the lending process that empowers financial institutions to incentivize meaningful change, whether regenerative agriculture, better water use, or leveraging water markets.

The real problem is that we planned pretty well in the past for crises like this, but we weren’t hamstrung by the push to decarbonize. Just putting up wind and solar without planning for the infrastructure needed to efficiently employ them, or without the hydro and small modular nuclear plants that should be buffering them instead of gas or the dream of sufficient batteries that is decades away, means we are at the mercy of Nature.

And She’s not too happy with us at this point.