PORTO, PORTUGAL - 28 MAY : A general view of an inflatable Champions League Trophy on display in ... [+]

Manchester City owner Sheikh Mansour’s motivations are always being discussed.

With every significant achievement his team makes; from scooping a domestic treble to reaching the Champions League final, there is always that question: Why?

Why would a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family choose to sink his wealth into a team from a cold, wet city in Northern England?

The relentless speculation is in contrast to Roman Abramovich his counterpart at Chelsea, who they face in this year’s Champions League final.

Early into his reign the Russian faced questions about his motivations for owning a club, but has rarely been subjected to such debates since.

Mansour on the other hand has had greater scrutiny the more time has passed.

Despite him almost never speaking to the media, the public perception around is intentions has evolved.

The idea of City as the trophy asset of a wealthy individual is gone, replaced by the theory that the club is PR tool for a nation with a questionable human rights record.

It is the country, apparently, that owns the club.

So ingrained is the theory Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp will casually reference, describing his his rivals “owned by countries, owned by oligarchs.”

But it is not accurate.

Nearly a quarter of the club is not actually owned by Mansour because he has been proactively selling stakes to major investors as it has grown.

In 2015 13% was sold to a consortium of Chinese investors for $400m, this was followed by the sale of just over 10% to American private equity company Silver Lake in 2019.

The board has representatives from these investors and while Mansour retains overall control, their involvement is no gimmick.

Worth 2,000 times more

Manchester City owner Sheikh Mansour with chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak (left) during the Barclays ... [+]

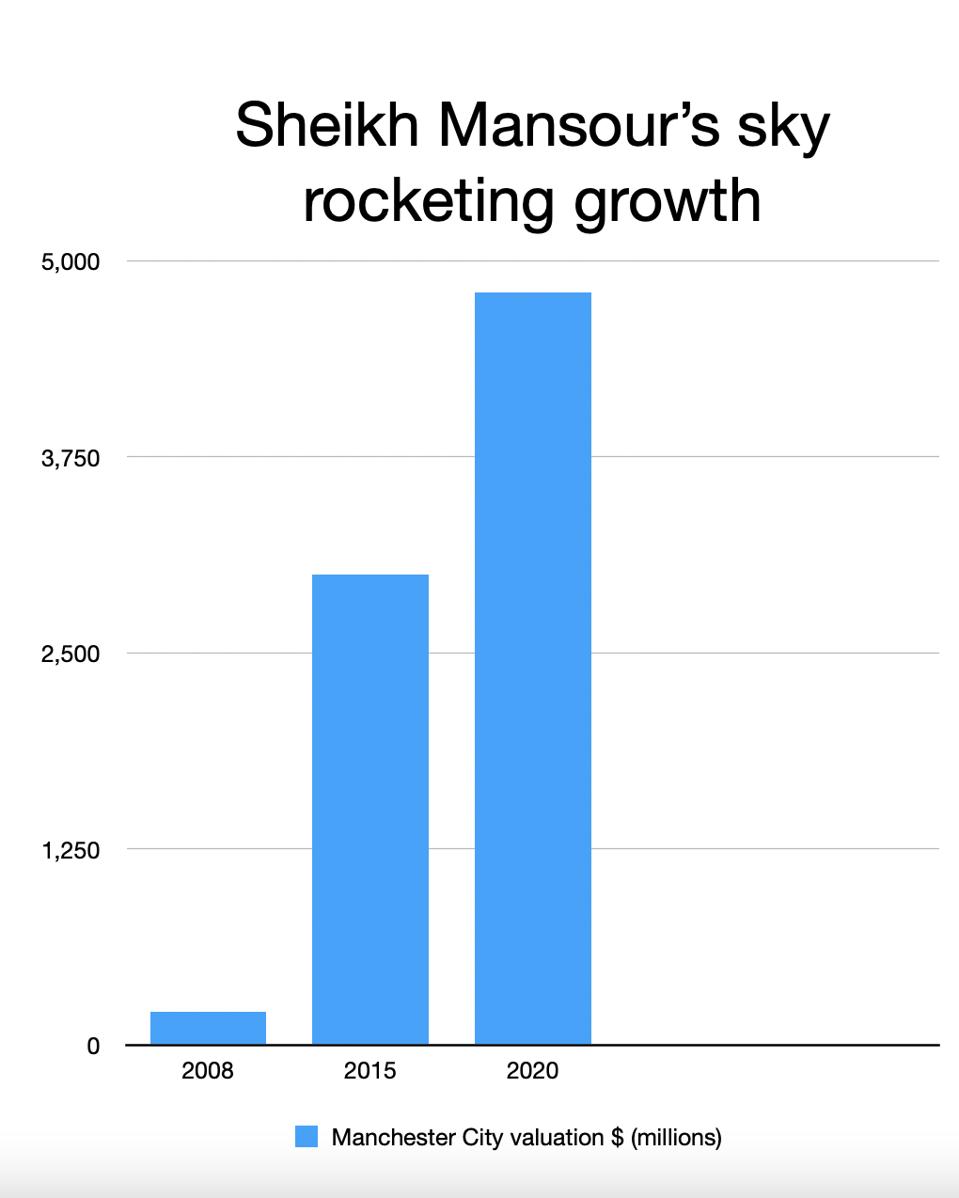

It’s strange that the massive increase in the value of the club almost never gets mentioned, when considering Mansour’s investment.

When you look at the numbers the Sheikh’s $212 million takeover in 2008 looks pretty savvy business.

Since then, accounts show he has invested $1.8 billion to lift the club from mid-table also-rans to all-conquering giants.

But this has resulted in the club being worth nearly $5 billion.

Bear in mind he has also netted close to a billion in the two stakes sold, which offsets a substantial portion of that investment.

City, the coronavirus season notwithstanding, now turns a profit, so the role of the owner essentially becomes more about offering a lending facility that keeps the club debt free.

As the years go on the gains are likely to be bigger, because the heavy investment has already been made.

In addition to the thriving team of superstars and growing fanbase, they have arguably the best sporting infrastructure of any club in the world and pioneering a network of global sister clubs.

A graph showing the increase in value since Sheikh Mansour acquired Manchester City back in 2008

If Mansour wants to earn some money from the club, as he has shown in the past, he can sell another stake.

Were he to part with the club entirely his profit would be vast.

Takeovers aside, the other investors will be expecting further growth and, more importantly, return on investment.

The City Football Group model of multi-club ownership is unique amongst elite clubs and offers opportunities in markets with more growth potential that other teams don’t have.

Failed European Super League aside, there are also likely to be further gains for Manchester City in Europe.

"I’m not sure that [CIty Football Group] CFG ultimately wants to sell,” says University of Liverpool expert in soccer finance Kieran Maguire.

“I think by happy that they will reap the rewards in a non-financial sphere.

“But there are also opportunities for the junior partners such as the Chinese partner to make a financial return on City in the long term.

“If we move to this expanded Champions League, in which they’re going to then having a team which is likely to be very successful, then all of a sudden it will be very lucrative.”

‘fairytale’ ownership

The Jack Walker statue outside the ground before the Sky Bet Championship match at Ewood Park, ... [+]

As the reaction to the European Super League showed, in Britain the idea of soccer as business is very unpopular.

Despite the men in suits taking over the game a long time ago, the belief that club ownership being an emotional investment persists.

The idea of a rich fan passionately sinking piles of cash in their boyhood club is romanticised and the various examples of British tycoons who used their wealth to buy success are eulogised.

From Jack Walker bankrolling Blackburn Rovers to the Premier League

Foreigners who showed up intent on doing the same have been viewed with suspicion, which is odd because there were plenty of examples of British owners who bought clubs they were not connected to.

Whether that’s Liverpool-mad Steve Morgan buying Wolverhampton Wanderers or Queens Park Rangers fan Ken Bates acquiring Chelsea, having a longstanding connection to the club has never been a given.

And for the fans ultimately the popularity of an owner at a particular club, like a player, has always come down to ‘how much they put in.’

Fans demand a 110% whether that’s the full back making a tackle or an owner going $1 million more to sign a player.

It’s why the European Super League backlash against the ownership of Arsenal, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur was more severe compared to Chelsea and Manchester City.

The perception is their owners were taking money out rather than putting it in.

Like it or not there is always a business angle and on that basis Sheikh Mansour has done pretty well.