An Exyn Technologies autonomous drone

No pilot?

No problem.

Exyn Technologies says it’s achieved the highest level of drone autonomy ever, which the company has classified at autonomy level 4A. That’s two levels short of full autonomy, but it does enable sophisticated transport, delivery, security, inspection, and research tasks, as well as new collaborative modes with other drones as well as land-based robots.

“The operator’s just giving very, very high level mission parameters to the drone and leaving it to the drone to figure out how it’s going to fly itself — not just going from point A to point B, but just figuring out how it’s going to complete the mission from there,” Exyn CEO Nader Elm told me on a recent episode of the TechFirst podcast. “We call this ‘Scoutonomy’ and we’ve just launched the first iteration of that, and that’s our Level 4A.”

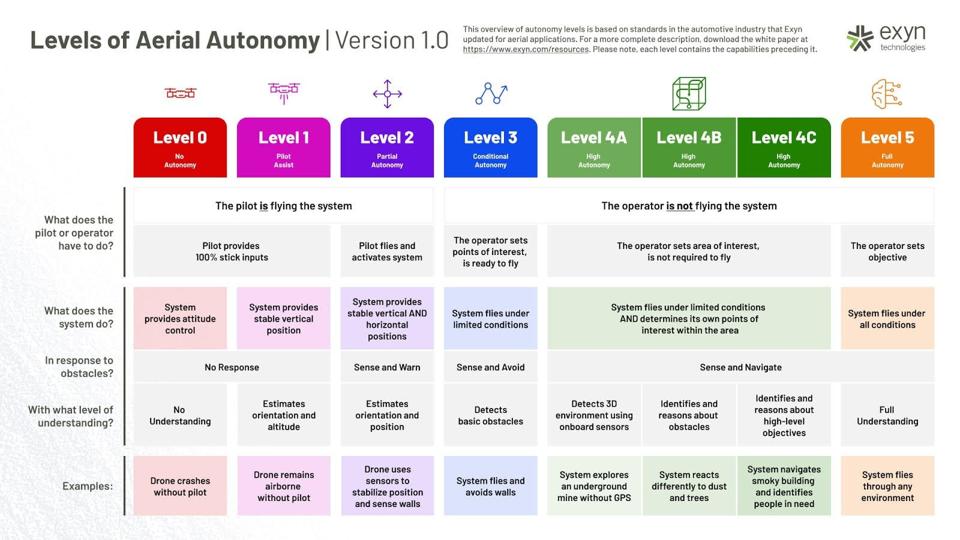

Level zero, as you might expect, is a pilot flying a drone.

So are levels one through three, although they add increasing doses of automated stabilization, crash avoidance, position sensing, as well as pilot assistance and warnings as you progress through those levels. My cheap consumer DJI drone, for example, will beep when it’s approaching obstacles, refuse to fly in no-go zones, and so on.

Level three is where a drone starts to get a destination from an operator and begins to fly itself, sensing and avoiding obstacles, at least in some limited conditions.

Level four and five are different: operators set areas of interest and the drone then senses and navigates itself in 3D space using onboard sensors. As Exyn has defined level 4, drones at this level of sophistication can map underground mines, react appropriately to real obstacles like trees and imagined obstacles like dust or fog, or navigate a smoky building to find people in need of help.

A drone autonomy chart showing levels of drone autonomy from zero to level 5.

Only in level five, full drone autonomy, can a drone fly under all conditions in any environment, however. Exyn says it has now achieved level 4A, which it defines as “high autonomy.”

This level makes drone automation much easier for routine inspection tasks like inspecting a bridge for damage or wear, Elm says.

“You just need to know roughly where the bridge is,” he told me. “You need to instruct the robot to say, ‘Okay, it’s between here and here, and it’s a cube or a kind of a stretched area,’ and leave the robot to figure out how it’s going to span the bridge, go and cover the bridge completely, and know when it’s done and return to base.”

Listen to the interview behind this story:

The analogy is teaching a child versus working with an adult: a child might have to be told each step and walked through all the components of each step, where an adult might just need to be told the objective and left alone to figure it out.

Exyn says its drones are accomplishing level 4A autonomy at 2 meters/second (around 4.5 mph). A single flight can cover 16 million cubic meters: the equivalent of nine football stadiums. In flight, the drones are completely self-sufficient, no requiring waypoints or human intervention, and no human operator is required to be ready on standby to take control at any instant.

Eventually, they'll do that at faster and faster speeds.

“Exyn’s latest technology demonstration pushes the boundary of what can be done with autonomous flying systems in situations where GPS is not available,” says University of Pennsylvania professor Camillo J. Taylor. “Getting aerial systems to fly reliably in cluttered environments is extremely difficult and manual piloting in underground settings is often impossible. Having a solution that allows human operators to task these systems at a very high level without needing piloting expertise opens up a number of applications in autonomous inspection of mines and other critical infrastructure.”

Exyn says autonomous drones have been the missing link for inspection work as well as search and rescue. Using machine learning models, the drones can be trained to look for specific things — like rust or cracks on a bridge — and take specific actions when found, like zooming in, or marking it for human review.

That opens up very interesting opportunities in autonomous security, where you can program a drone to take a circuit of a building every 20 or 30 minutes — or a random time intervals — as well as search and rescue.

And it opens up possibilities in collaborative drones that Exyn is working on.

“There’s things that we want to do to make it faster, make it higher resolution, make it more accurate,” Elm says. “But the other thing we were kind of contemplating is basically the ability to have multiple robots collaborate with each other so you can scale the problem, both in terms of scale and scope. So you can have multiple identical robots on a mission, so you can actually now cover a larger area, but also have specialized robots that might be different. So, heterogeneous swarms so they can actually now have specialized tasks and collaborate with each other on a mission.”

And that’s where autonomous drones get extremely interesting.

Being able to program a set of drones and robots for a collaborative task that they can communicate on, subdivide, and work together to achieve autonomously opens up a huge number of use cases: industrial, shipping and receiving, or search and rescue. A fixed-wing drone with thermal imaging capability, for instance, might pinpoint areas that more nimble quadcopter drones should investigate. They can go below a forest canopy, for instance, and hover in place to get very clear imaging.

Over time, that will be possible with less and less human intervention required.

“You can instruct individual [drones] to do one and then two and then three, or an objective for a team where you’re basically saying, ‘Here is what I’m trying to achieve … now leave it to the rest of the team to figure out how that’s going to be done, and break down the problem.’ And that is exactly what we’re trying to do,” Elm says.

Subscribe to the TechFirst podcast, or get a full transcript of our conversation.