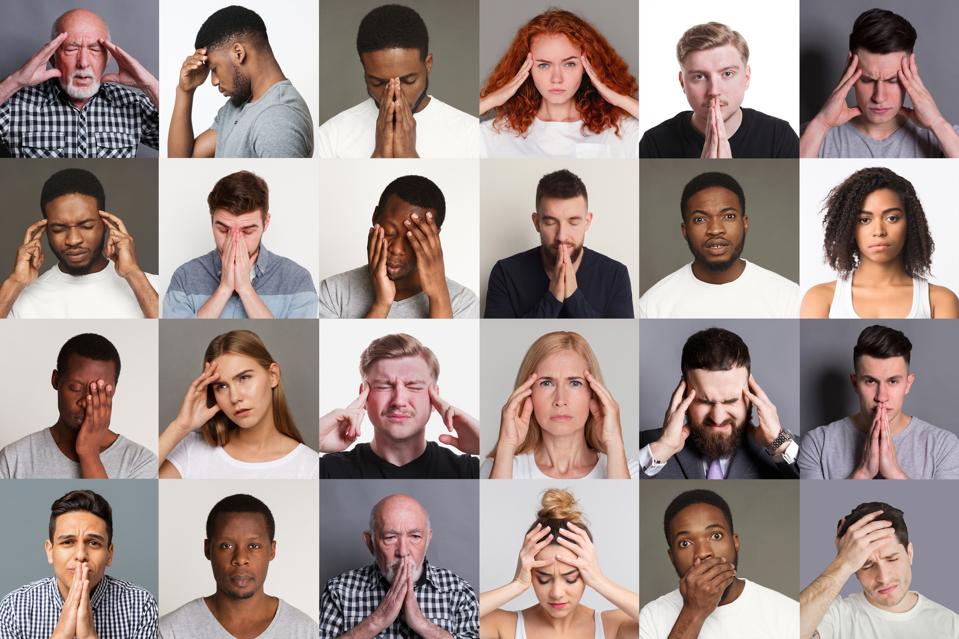

Appalachians suffer from high rates of mental illness, substance abuse, and poverty - all factors ... [+]

West Virginia boasts lush mountains, rolling hills, and a wide variety of wildlife. But underneath this natural beauty, there’s a darker side to West Virginia. The state has one of America’s highest suicide rates. This statistic has climbed since 2009, leaving more mourning families every year.

To address Appalachia’s suicide rate, health advocates are studying several factors that contribute to the region’s distress.

Mental Illness in the Mountains

Many Appalachians face mental illnesses like depression and anxiety but lack mental health ... [+]

Loneliness, depression, and substance abuse are ravaging rural communities in Appalachia.

Economists and psychiatrists have called these conditions “diseases of despair” since mental illness and drug dependence can lead to suicidal ideation. Appalachians tend to suffer from more mental illnesses than do people who outside of the region, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

People who are addicted to alcohol or drugs are also more likely to attempt suicide; 70% of adolescent suicides are linked to substance abuse. States like West Virginia, Ohio, Tennessee, and Kentucky have the highest rates of opioid use in the nation, an epidemic of drug dependency and abuse. Patients who use opioids, such as prescription painkillers or heroin, are especially at risk for suicide, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration warns.

When Appalachians are struggling with mental illness and substance abuse, where can they find treatment? Many Appalachian towns are nestled high in the mountains, far from medical services like counseling offices or crisis centers. Towns in the most rural areas of Appalachia have 50% fewer mental health professionals than the national average.

The dearth of mental healthcare and high instance of mental illness make a deadly combination.

Gun Access in Hunting Country

Many people in the region have access to firearms, which can turn suicidal ideation into a deadly ... [+]

Gun culture is strong in Appalachia.

Gun shows in the region can attract thousands of attendees. Among the most infamous is the Hillsville flea market. Twice a year, the tiny town of Hillsville, Virginia hosts one of the largest flea markets in the United States. One section of this market is nicknamed “Gun Hill” or “Gun Alley”. Vendors carry, barter, and sell firearms: no ID needed. Sellers often provide discounts for buyers who use cash. While authorities have attempted to crack down on “Gun Hill” at Hillsville, the tradition is deep-rooted in years of sales.

When a suicidal person has access to a firearm, they have a potential tool to harm themselves. Men who have a gun in their home are eight times more likely to commit suicide than men who don’t own guns. Women who have guns are 35 times more likely to kill themselves than women without firearms.

For many Appalachians, guns are practical, not nefarious. Scores of families use their firearms to hunt or to protect their livestock from predators. But this easy access to guns can catalyze suicide attempts in a region that’s already overburdened with mental illness.

Outreach Efforts to Preserve Life in Appalachia

Mental health organizations are working to save lives in these rural mountain towns.

The Appalachian Telemental Health Network (ATHN) was founded to bridge the geographic gap in mental health coverage in Virginia. Some Appalachians may not live within commuting range of a mental health provider. Residents can visit the ATHN website to make telehealth appointments to video chat or call a therapist.

While telehealth networks can reach people in remote locations, programs like the ATHN cannot serve people who live without internet access. Up to 25% of Appalachians do not have a computer, say the authors of a Population Reference Bureau report about rural technology access.

These people who don’t have internet often consult a family doctor about their mental illness. A study in the American Journal of Psychiatry revealed that almost half of victims had contacted their primary care provider in the month before they attempted suicide. Many doctors feel the pressure to recognize warning signs in their patients, although few doctors in Appalachia are formally trained in psychiatry. For example, a family doctor named Dr. Joanna Bailey works in West Virginia. In an interview with the Kaiser Family Foundation, Bailey said that there were no psychiatrists or therapists working in her county: “As a family doctor, I’m doing way more psychiatry than I am comfortable with.” Without this psychiatric training, doctors may not know how to recognize or respond to a patient’s suicidal thoughts.

Some mental health advocates are turning to grassroots efforts. Community members support one another in peer support groups in church fellowship halls. Local health departments host wellness sessions. And clinics and hospitals are hiring more psychiatrists to host impromptu therapy sessions and to immediately address patients’ mental health concerns.

While Appalachians faces numerous challenges, many hope for a brighter future free from suicide. If you or a loved one is at risk of suicide, please call the national helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357). This service is free and confidential.