When the term “vaccine” comes up in conversation, especially in recent months, it’s typically referring to the vaccines against the Covid-19 coronavirus. Prior to the pandemic, people often talked about vaccines in reference to the flu, measles, mumps, etc. But there’s one type of vaccine that, although not often a topic of frequent discussion, actually has one of the largest potential impacts: it may actually decrease rates of some forms of cancer.

This is the vaccine for human papillomavirus, which is more commonly known as HPV. HPV infections have been long been associated with forms of cervical cancer.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Almost all cervical cancer is caused by HPV. Some cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and oropharynx (back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils) are also caused by HPV […] In general, HPV is thought to be responsible for more than 90% of anal and cervical cancers, about 70% of vaginal and vulvar cancers, and 60% of penile cancers.”

WASHINGTON, DC - NOVEMBER 20: U.S. President Barack Obama (2nd R) prepares to present John Schiller ... [+]

The CDC adds that "The HPV vaccine does not substitute for routine cervical cancer screening tests (Pap and HPV tests), according to recommended screening guidelines.” However, “The HPV vaccine protects against the types of HPV that most often cause these cancers.” Importantly, it notes that “HPV vaccination prevents new HPV infections, but does not treat existing infections or diseases. This is why the HPV vaccine works best when given before any exposure to HPV.”

HPV infection is not an uncommon phenomenon. In a statement released yesterday, the UVA Cancer Center explained that “Nearly 80 million Americans – 1 out of every 4 – are infected with HPV, a virus that causes several cancers. Of those millions, more than 36,000 will be diagnosed with an HPV-related cancer this year.”

But the press release raises another critical concern. It mentions that “Despite those staggering figures and an available HPV vaccine, HPV vaccination rates remain significantly lower than other recommended adolescent vaccines in the U.S. […] According to 2019 data from the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC), only 54% of adolescents were up to date on the HPV vaccine, while a 2019 CDC report found that more than 90% of U.S. children were vaccinated against Hepatitis B as well as measles, mumps and rubella.” These numbers have only become worse, due in large part to the pandemic. According to UVA’s statement, “Early in the pandemic, HPV vaccination rates among adolescents fell by 75%. Since March 2020, an estimated 1 million doses of HPV vaccine have been missed by adolescents with public insurance – a decline of 21% over pre-pandemic levels.”

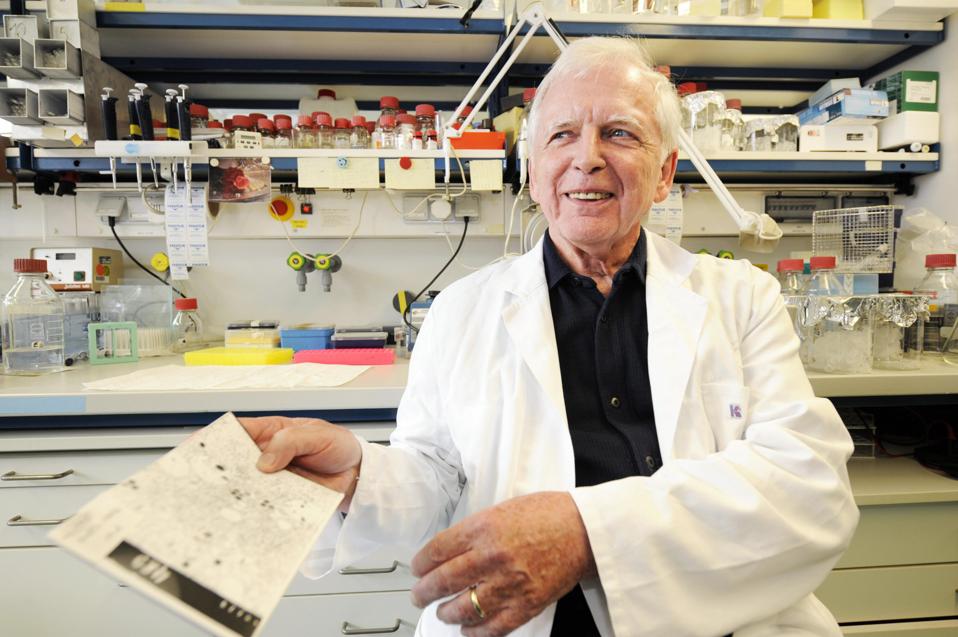

German scientist Harald zur Hausen poses on October 6, 2008 in his former laboratory at the cancer ... [+]

Indeed, if patients continue to ignore this phenomenon, it may lead to a public health fiasco that’s relatively preventable, especially given the dire consequences that HPV infection can result in.

This should not be considered medical advice or be taken as a professional recommendation. As with anything related to patient care or medical treatment, it’s always best to speak with each individual’s physician and get professional medical advice that is specific to each patient’s unique situation and medical history. This is especially true as there may be some outlying situations or patient issues that need to be considered. Thus, patients should always consult their physician first to find out more and see if this is an appropriate decision. Regarding vaccination guidelines, as of when this article is written in May 2021, the CDC states that “HPV vaccination is recommended for preteens aged 11 to 12 years, but can be given starting at age 9. HPV vaccine also is recommended for everyone through age 26 years, if they are not vaccinated already. HPV vaccination is not recommended for everyone older than age 26 years. However, some adults age 27 through 45 years who are not already vaccinated may decide to get the HPV vaccine after speaking with their doctor about their risk for new HPV infections and the possible benefits of vaccination. HPV vaccination in this age range provides less benefit, as more people have already been exposed to HPV.”

As a general rule of thumb, community healthcare outcomes are usually better when societal emphasis is placed on proactive rather reactive medicine. That is, why treat something, when it could have been prevented in the first place? This is the incredible paradigm made possible by vaccinations. With regards to HPV and declining vaccination rates, there must be increased patient awareness and community education, so that a potentially looming yet preventable public health-crisis is mitigated.

The content of this article is not implied to be and should not be relied on or substituted for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment by any means, and is not written or intended as such. This content is for information and news purposes only. Consult with a trained medical professional for medical advice.