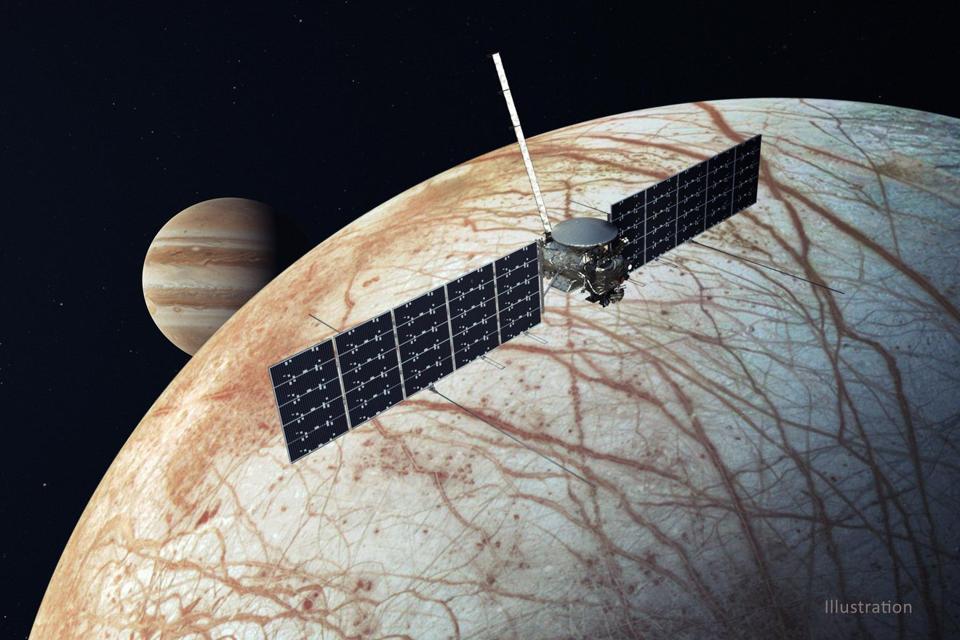

This illustration, updated as of December 2020, depicts NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft. The ... [+]

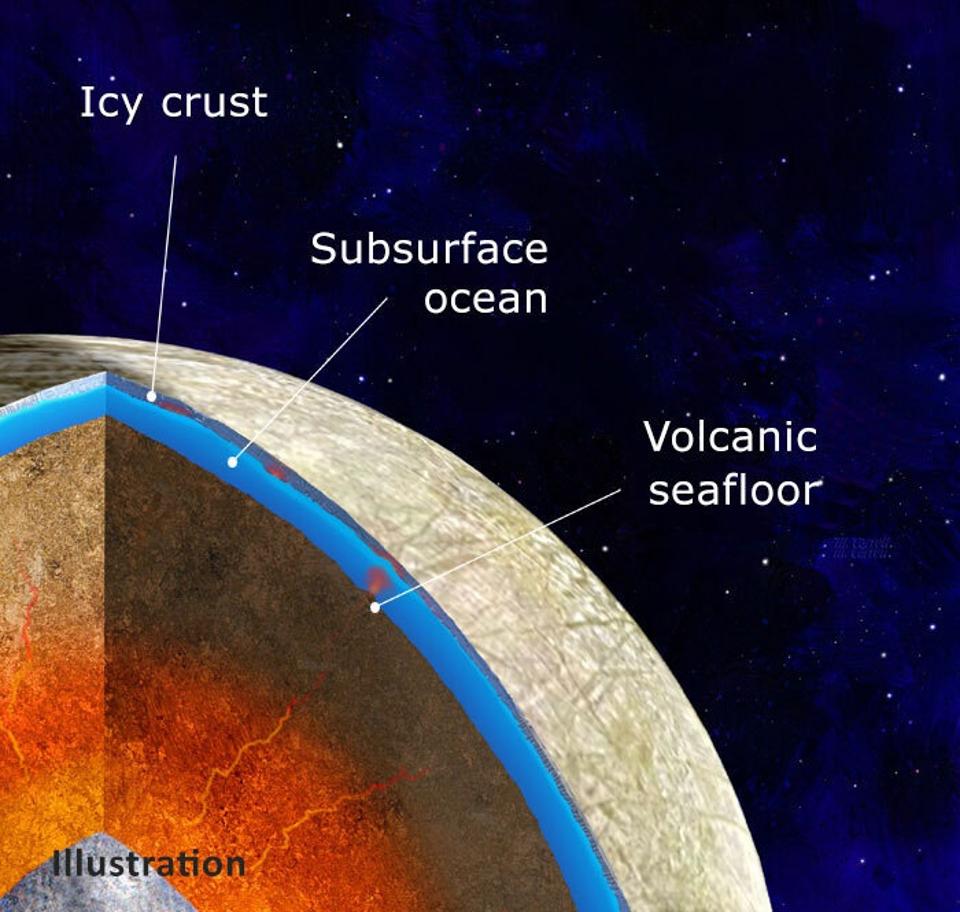

Europa —- Jupiter’s fabled, frozen moon —- may have an interior that’s hot enough to create seafloor volcanoes which NASA hopes its upcoming Europa Clipper mission will ultimately detect. If so, they would incredibly lie beneath a hidden global ocean squeezed between Europa’s global icy crust and the moon’s rocky interior.

Yet the authors of a recent paper in the journal Geophysical Research Letters detail new modeling that shows volcanic activity may have occurred on Europa’s seafloor in the recent past – and may still be happening, says NASA. And the idea is that the Europa Clipper, an interplanetary orbiter due for launch in 2024, will make its way to the outer solar system and swoop close enough to Europa’s surface to collect measurements that could confirm these new undersea computer models.

We have found life deep at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, at hydrothermal systems where water circulates through hot rock where it is heated and absorbs chemicals from the rock layer, Cynthia Phillips, a planetary geologist and Europa Project Staff Scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told me. “If seafloor hydrothermal systems do exist on Europa, they could be sources of thermal and chemical energy that could support a biosphere,” she says.

Even so, the key to Europa’s rocky mantle being hot enough to melt lies with the massive gravitational pull Jupiter has on its moons, says NASA. As Europa revolves around the gas giant, the icy moon’s interior flexes which forces energy into the moon’s interior, which then seeps out as heat, says the space agency. This new paper models in detail how Europa’s rocky part may flex and heat under the pull of Jupiter’s gravity and shows where heat dissipates and how it melts that rocky mantle, increasing the likelihood that Europa may have volcanoes on its seafloor, NASA notes.

Europa’s ice crust is estimated to range between a few kilometers up to several tens of kilometers thick. Yet the moon’s polar regions is where the paper’s authors think heat produced by tidal friction may be the largest. If so, they write that the release of seafloor heat in these polar regions should also be accompanied by the release of chemical compounds that could impact the moon’s ocean chemistry.

Scientists’ findings suggest that the interior of Jupiter’s moon Europa may consist of an iron core, ... [+]

Once the Europa Clipper spacecraft arrives, its thermal E-THEMIS imager will be able to detect temperature anomalies on Europa that could correspond to subsurface volcanic activity. The spacecraft will also take gravity measurements, which could detect gravity anomalies and provide clues about potential volcanic activity.

“Europa is one of the rare planetary bodies that might have maintained volcanic activity over billions of years, and possibly the only one beyond Earth that has large water reservoirs and a long-lived source of energy,” lead author Marie Běhounková of Charles University in the Czech Republic said in a statement.

Underwater volcanoes, if present, could power hydrothermal systems like those that fuel life at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, says NASA. On Earth, when seawater comes into contact with hot magma, the interaction results in chemical energy, notes the agency. And it is chemical energy from these hydrothermal systems, rather than from sunlight, that helps support life deep in our own oceans, says NASA.

But it’s this global layer of ice that makes helps make Europa such a unique planetary body.

On Europa, the surface ice layer is likely at least 10 kilometers thick, says Phillips. On Earth, even the oldest sea ice is only meters thick, she says. So, any ecosystem on Europa would be completely isolated from the Sun, and would have to use other sources of energy to sustain itself, such as thermal or chemical energy, Phillips says.