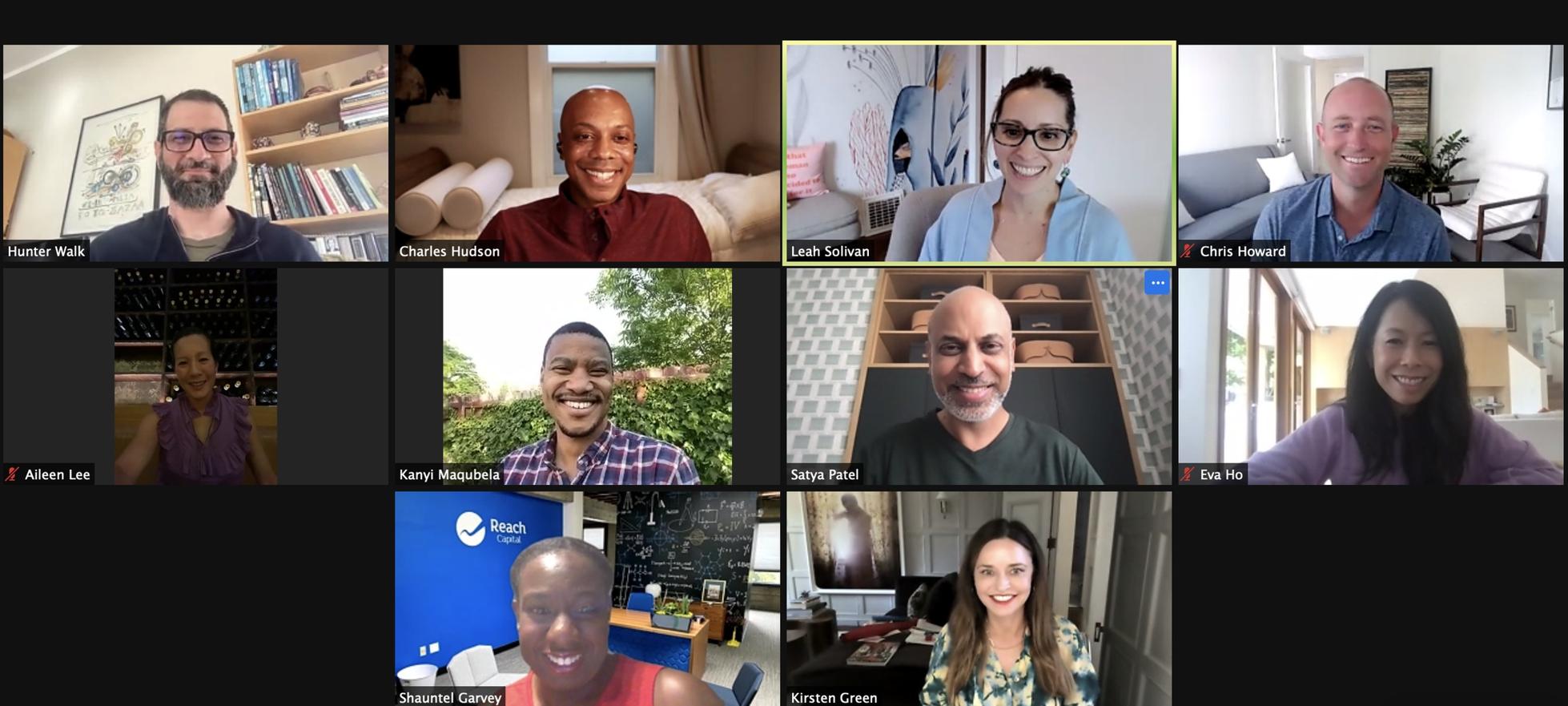

Screendoor's 10 founders teamed up across VC firms to launch a fund-of-funds to back emerging fund managers from underrepresented backgrounds.

ScreendoorWould-be venture capitalists looking to raise a fund for the first time often face a chicken-and-egg problem: to raise money, they’re expected to demonstrate a track record of promising startup investments; to build such a portfolio, they need to raise money.

It’s a challenge felt even more by emerging fund managers from underrepresented backgrounds, say Homebrew partners Satya Patel and Hunter Walk. “What we heard over the last few years as we got approached by new managers hoping to raise funds was that were plenty of opportunities for them to get counsel or mentorship, but what they really needed was capital,” Patel says.

Now, Patel, Walk and eight other general partners at established VC firms are trying an experiment: raise their own fund together, across firms, to bring the resources of some of the industry’s elite limited partners into emerging funds faster. Called Screendoor, the fund is a $50 million-plus investment vehicle that will look to back up to 15 underrepresented investors raising their first institutional fund, all while providing formal and informal training and support without drawing carry or fees.

The ten partners behind Screendoor include Aileen Lee of Cowboy Ventures; Eva Ho of Fika Ventures; Kirsten Green of Forerunner Ventures; Chris Howard and Leah Solivan of Fuel Capital; Patel and Walk at Homebrew; Kanyi Maqubela of Kindred Ventures; Charles Hudson of Precursor Ventures; and Shauntel Garvey of Reach Capital. The institutions investing in Screendoor include the investment arms of Davidson, Duke, Harvard, Michigan, Princeton and Virginia; The James Irvine Foundation; and investment firms Hall Capital and Sapphire Partners.

By pooling the capital in a fund-of-funds like Screendoor, such institutions can invest and build relationships with new fund managers they wouldn’t otherwise be able to back, Walk says, as first-time funds often raise amounts too small for a university endowment or large foundation’s VC strategies. Every limited partner in Screendoor is an investor in at least one of the firms represented by Screendoor’s founders, meaning Screendoor’s partners can use their own reputations as a bridge. “This can be a training ground for emerging managers to scale ahead of direct relationships with some of these larger institutions,” Walk says.

And while Screendoor’s own general partners are VCs themselves and thus potential co-investors and peers, the investors they back will not be asked to share deal flow or more information than they would with a typical LP. Screendoor will make investments through a rotating investment committee of three, starting with Patel, Hudson and a representative of its limited partner The James Irvine Foundation. “Screendoor promises access to talented emerging managers and allows us to begin a relationship with these investors ahead of their first institutional raises.

“We’re participating not just as capital partners but will contribute time as well, alongside the hands-on mentorship Screendoor managers will receive,” Jesús Argüelles, the foundation’s director of investments, said in a statement. “Over time I hope we’ll build direct relationships with many of these firms.”

Screendoor is launching as a wave of new funds and initiatives are picking up in the venture industry, historically slow to major change but galvanized over recent months since the death of George Floyd. Those include the launch of funds from Zane Venture Fund and Collab Capital in Atlanta; a new fund from Harlem Capital in New York; MaC Venture Capital in Los Angeles; and Sixty8 Capital in Indianapolis, among others. And other programs, such as a new scout program launched by BLCK VC with Lightspeed and Sequoia, have looked to inject more investors into the ecosystem.

But such progress has been incremental at best, still a relative drop in the bucket compared to billions raised by traditional funds. That has shut such investors out of what Patel calls Silicon Valley’s “virtuous cycle,” in which investors back tech companies that in turn churn out more successful angel and venture investors as they exit. “The unfortunate part is that virtuous cycle has been inaccessible for large portions of the population,” Patel says.

Screendoor hopes to help set up its own virtuous cycle of underrepresented investors backing underrepresented founders who elevate underrepresented employees. But it doesn’t presume to have all the answers. Screendoor’s organizers will “open-source” their process for any other groups looking to emulate or improve upon it, Patel and Walk say; they also plan to expand Screendoor’s investor group with future funds.

Screendoor is in talks with some prospective fund managers already, but the group haven’t made any commitments yet. Interested investors will be able to apply via open application on the fund’s website; what constitutes an underrepresented background or first institutional fund is flexible. “Anybody who believes that they are bringing something to the ecosystem that is currently underrepresented by the way capital has flown within venture, they have a chance to tell us about that,” says Walk.

And while Screendoor’s partners aren’t taking fees or carry in the fund, it’s not intended as charity. The fund will hire a full-time analyst or similar role to manage its portfolio and structured training and advice offered by its partners. And with those partners’ own LPs backing Screendoor, everyone involved expects a financial success. “The investors in the fund aren’t investing out of charity, they expect industry-beating returns here,” Patel says.