LONDON, ENGLAND - JUNE 12: Performers operate a puppet wearing designs by Aitor Throup on the ... [+]

I want every risk-taking designer to be Aitor Throup because in the 22nd century I want, most of us are watching Premier League football in a pub orbiting Ganymede. We wear flame-retardant football home kit updated for The Fifth Element. Shin guards are enormous, titanium, but no longer compulsory. Orbiting starships are built from programmable matter. Their hulls wrap across skeleton bulkheads like something organic growing from the inside out. I don’t mean to suggest that Throup’s work envisions a different world than our own, something science-fictional in that sense. To the contrary, what’s drawn me to Throup’s work, starting with his designs for ‘When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods,’ is its ability to defamiliarize the everyday and imaginatively extrapolate its possibilities. How does he do that? Throup’s latest multimodal project, ‘Anatomyland,’ is an unfolding ars poetica that uses digital sculpture as a springboard for exploring how existing designs and objects generate their own organic meanings.

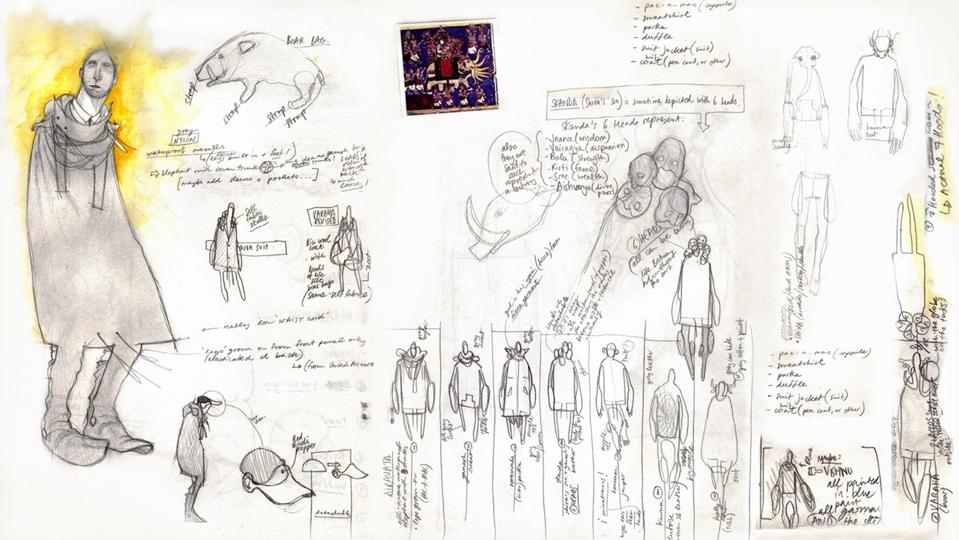

Drawings for the collection 'When Football Hooligans Become Hindu Gods'

I spoke to Throup recently on a video call. Throup has launched prototypes of his Anatomyland digital sculptures as nonfungible tokens (NFTs) on Nifty Gateway. A second phase consists of two pieces, ‘Modular Veil Cap’ and Modular Bucket Hat,’ released in five units per design, with each artwork signed, numbered, authenticated, and linked to unique blockchain. As we spoke, the video began to freeze and unfreeze. As his frozen image continued to speak, I couldn’t help thinking it was fitting for a conversation about NFTs. But it also struck me that much of the discussion around Throup’s design stays at the textural surface of his work, whereas much of the discussion in Throup’s work is centered on what happens within the image – design processes, narrative dynamics. You have to let Throup’s images speak on their own terms.

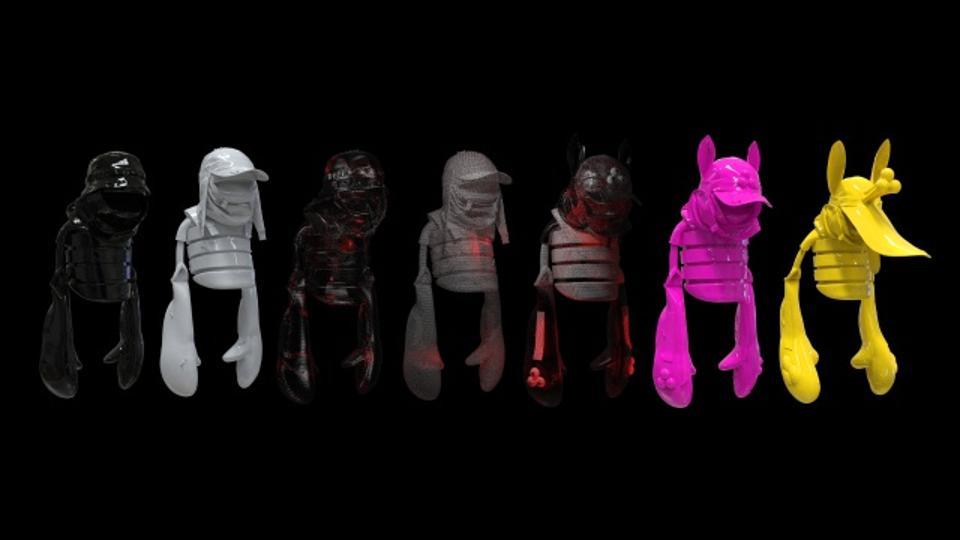

Anatomyland digital sculptures

Throup’s prototype figures represent different stages in an allegorical drama. Anatomyland, Throup reflects, is ‘about the nature of life, the nature of conflict, but all of this is wrapped up in an analysis of what constitutes human identity.’ In what Throup calls the design’s ‘ritualistic space,’ two figures named ‘Lil Yin’ and ‘Lil Yang’ represent opposing positions in binary relationships – masculine and feminine, black and white, explosive and defensive – while a third, ‘Good Ol’ Dom’ (G.O.D.), serves a fitting deus ex machina function, offering viewers a ‘shared conceptual objective,’ a ‘singularity in function’ for the project’s themes.

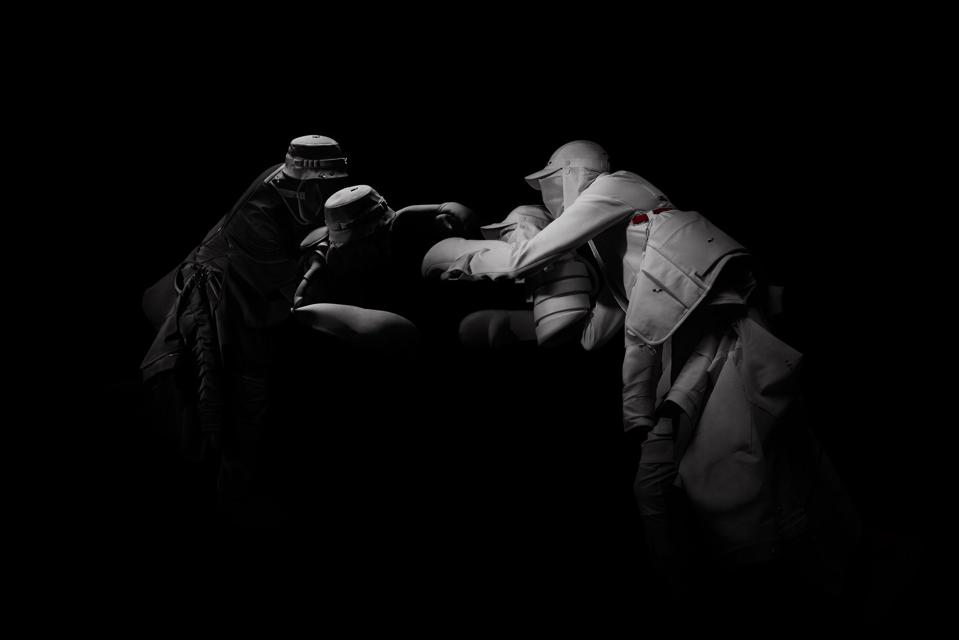

Anatomyland, Lil Yin and Lil Yang in conflict

If you know the project’s themes, Throup’s figures are visual integers in his allegories. Lil Yin and Lil Yang, for example, articulate the point that ‘the core of our unhappiness’ is that we see ourselves and others in ‘these two pockets, representations of these personae.’ Fittingly, both figures are designed to be earless and eyeless. They can only shout at each other. Good Ol’ Dom is an epithetical skeleton, a ‘cartoon, child-friendly Death.’ He signifies their resolution and synthesis as a ‘symbol of our equality.’

Anatomyland, Good Ol' Dom

In organizing Anatomyland as allegory, Throup assumes real imaginative risk. On the one hand, Throup’s concept is a highly personal exploration of social belonging and artistic growth. ‘I’ve always struggled to fit in,’ the Argentinian-British artist reflects, ‘and for the past 16 years I have devoted my life to creating a definitive world as an alternative to the one we’ve been told we exist in.’ In that sense, Anatomyland increases its stakes by also suggesting a ‘definitive’ lens for reconsidering Throup’s whole oeuvre, including his collaborations with Damon Albarn, Umbro, and G-Star Raw, his costume design for The Hunger Games and Wayne McGregor’s ‘Autobiography,’ New Object Research, and his Stravinsky-inspired photographic project, ‘Rites of Spring.’

PARIS, FRANCE - JUNE 23: Aitor Throup attends the G-Star Raw Research III Collection launch during ... [+]

At the same time, allegories always beg the question of their own raison d’être. Why not simply state the allegory’s thesis? Because the dramatic situations that comprise allegories exist in service of fixed messages, they tend toward static characterizations and predictable outcomes. This is what often makes traditional allegories like the ‘Everyman’ plays of the Middle Ages so tedious to read. A figure named ‘Greed’ will always be greedy. ‘Sloth’ is slothful. ‘Lust’ will never act chaste. No less a medievalist than J.R.R. Tolkien admitted to disliking the form ‘in all its manifetations’ precisely because it lacked ‘varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers.’ For Throup, though, the flatness of traditional allegorical representation is deliberately present as the landscape occupied by Lil Yin and Lil Yang. It’s ‘Anatomyland in terms of pointing to where the truth lies,’ Throup reflects, ‘the self within, the body within.’ In effect, the ritual drama of Throup’s design is intended to locate allegorical distinctions and then complicate them with the sort of unpredictable inward turn that Tolkien suggests.

Anatomyland. Lil Yang

In the best medieval allegories – William Langland’s Piers Plowman, for example – this sort of complication happened through sophisticated descriptive characterization. Because Anatomyland is a visual project, though, depth of experience is a compositional analogue to psychological characterization. ‘There are two kinds of creation,’ Throup explains, ‘from the outside in or from inside out. When you create from the outside in, it’s like a shortcut that makes us default to standardized solutions instead of imaginative ones.’ Consumer culture, Throup suggests, makes us reach for commodified allegories ‘using archetypes that already exist and decorating them because the value of the inside is hollow, only present in the original form.’ While the figures of Lil Yin and Lil Yang have fixed visual meanings as part of an allegorical conflict, their method of production critiques the same ‘outside in’ approach to value that we tend to encounter them with.

Anatomyland writ large, on the other hand, is an unfolding experiment with ‘inside out’ design. In practice, ‘inside out’ design approaches art as a ‘self-enclosed aesthetic system,’ one in which simply ‘having a system voids the creator to some degree.’ It’s a core, this is a philosophical argument that objects and their meaningful relationships – whether real or imagined – exist external to the human mind, a kind of ‘object-oriented ontology.’ It follows, then, that any artistic approach like Throup’s is potentially a critique of how we impose mental distinctions in our social, psychological, and spiritual lives. ‘You identify the thing that exists,’ Throup explains, ‘and what you want to do with it. The job of the artist is protecting the nucleus of the work as it develops because the idea dictates what it needs. You don’t know what you’re going to create, but the product could only look a certain way because it was dictating itself. The creator was only guiding it.’

Anatomyland digital sculpture

Under the surface of Anatomyland’s images, I thought, there’s a heady mix of philosophy and craft. Throup’s own image froze again onscreen somewhere between New York and the U.K. I walked around my apartment trying to catch signal. What Throup was talking about reminded me, at turns, of the old ‘Problem of Universals’ that obsessed medieval philosophers, Gerard Manley Hopkins’s idea of poetic ‘inscape,’ or the debates between John Crowe Ransom and Cleanth Brooks about whether a poem is more like a decorated Christmas tree or the hypostatic union. It was almost a self-generating conversation, ‘dictating itself.’ As Throup and I talked, one frozen image to another, I noticed a row of Star Wars stormtrooper figurines on the shelf behind him. ‘I like the reboot one,’ I said, ‘where the stormtrooper takes off his white helmet and you finally see him, face to face, beneath the shell.’