EVORA, PORTUGAL - SEPTEMBER 30: The famous warning at the entrance of the Capela dos Ossos (Chapel ... [+]

At Portugal’s Capela dos Ossos, Franciscan monks decorated the chapel walls with intricate patterns of 5,000 human bones and skulls. An inscription over the entrance reminds the living on behalf of the dead that ‘our bones await your bones.’ The chapel’s mirror effect is a core compositional principle in memento mori art. Artistically, death is always a mode of self-portraiture, but memento mori seeks to catalyze the shock of recognition as a means of contemplating a more virtuous life. The form’s secular origins date to the Stoics, but focusing on the ‘Last Things’ has also been a longstanding part of Catholic ascetic practice and devotion. In recent years, the rediscovery of Catholicism’s traditional forms of art, liturgy, and culture – often in surprising new iterations – has brought about renewed interest in the practice. The New York Times, for example, recently profiled author and modern-day maker of memento mori, Sister Theresa Aletheia Noble, as ‘the Nun Who Wants You to Remember You Will Die.’ It’s true, she does. But her second name, Aletheia, means ‘disclosure’ as well as ‘fact’ in Greek. It points toward memento mori’s relationship between recognizing the fact of mortality and inviting us into the process of self-examined living that death discloses. I recently spoke with Sister Theresa Aletheia about the form’s contemporary resonance.

Sister Theresa Aletheia Noble, FSP

Salyer: Social media offers so many composed images of lifestyles as real life. Simulacra. There’s something refreshing about seeing one of your posts that simply says: ‘you are going to die.’ How does a devotion like memento mori – one that’s very focused on the physical – translate into online culture?

Sr. Theresa: Death is taboo in our modern world. Even when we talk about it, we try hard not to, using euphemisms and saccharine platitudes. Perhaps because online activity is so mediated, it contributes to the scandalizing factor for people. For centuries, memento mori reminders were communicated in person, often with the very bones of the dead just feet away. Online reminders of death, on the other hand, suddenly show up in our social media feed and ruin our efforts at escapism. Memento mori returns us to our bodies, to our mortality, and to our real lives, and a lot of us go online to escape just that. So maybe online memento mori reminders are quite fitting in that way. Memento mori is supposed to return us to reality, to our bodies, to the linear nature of our lives, and to what is real and most important.

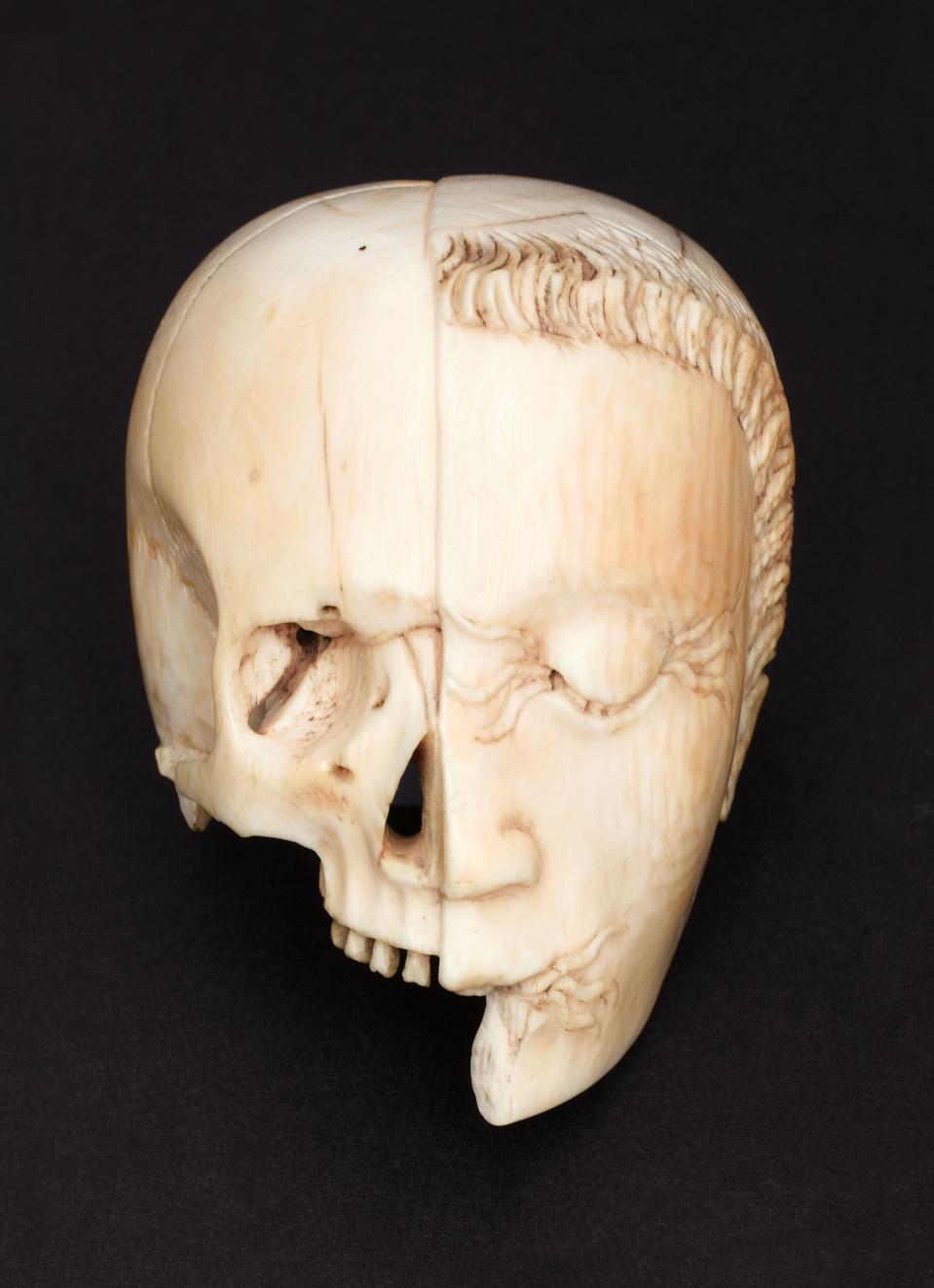

UNITED KINGDOM - SEPTEMBER 20: Ivory memento mori. Europe, 1601-1900. Ivory model of a half head, ... [+]

Salyer: Is there a way in which the process of making memento mori books and art, as the Daughters of Saint Paul do, helps ‘return us to reality’ like you’re saying? Crafting something’s a physical process. On the other side of that, does contemplating something with the senses – seeing or touching death’s reminders, for example – help us understand beauty differently?

Sr. Theresa: The Daughters of St. Paul (informally known as “media nuns”) get really excited about books because our missionary work for many decades has been centered in publishing. So after I started tweeting about my practice of daily meditation on death and people began to ask for resources to take up the practice, we were prepared to respond. I then worked with my sisters to create a memento mori journal, a Lenten devotional, a prayer book, and an upcoming Advent companion.

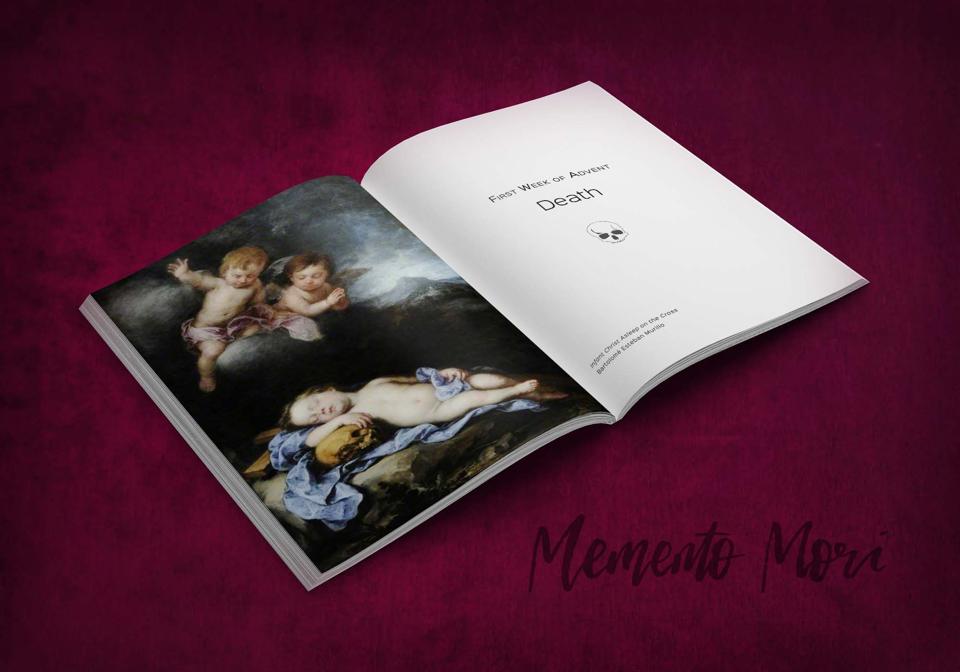

Memento Mori: Advent Companion on the Last Things

From the beginning of the projects, I knew symbolism and design would be just as, if not more, important than the words I wrote. After all, in many cases, memento mori traditionally has been more about symbolism than words. Sr. Danielle Victoria Lussier, FSP, understood this and worked with me to create a skull design for the covers of the books that is rich in symbolism.

My soon-to-be-released book, Memento Mori: Advent Companion on the Last Things, will be the culmination of Sr. Danielle Victoria’s contribution. She has asked over twenty living artists to contribute their memento mori-inspired art to the book. Unlike the other books, it will be in full color. In a way, that’s more appropriate to memento mori. One might associate meditating on death with black and white, dour imagery, but this practice actually allows us to live in full color. It gives hope, joy, and, maybe strangely, even comfort.

Memento Mori: Advent Companion on the Last Things

Salyer: In Latin, memento’s in the second person – ‘you remember that you’ll die.’ Thinking about that metaphor of living in black-and-white versus ‘full color,’ it strikes me that a skull’s a universal image, something you could screen print or tattoo, but my own death is a very personal experience. If memento mori prompts that ‘full color’ personal awareness, how does someone then structure it into daily life?

Sr Theresa: I had this same thought when I first began my journey with memento mori! After I got a ceramic skull for my desk, I very quickly realized that, rather than serving as a potent reminder of my own death, the skull could easily just become an overlooked part of my office décor. That’s why I began to share my journey publicly online; it began simply as a means to get me into the habit of meditating on death.

Sr. Theresa Aletheia Noble, FSP, with memento mori

Saint Benedict, the founder of Western monasticism, exhorted his monks in his Rule to “keep death daily before one’s eyes.” Daily, regular meditation on death is what helps keep memento mori personal. We can easily turn reminders of death into white noise if they don’t prompt us to prayer and deep thought. That’s why it’s important to consciously integrate memento mori as a practice into one’s life.

Sometimes people get really concerned about meditating on death correctly, but meditating on death is very simple. It mostly involves simply bringing the idea of your eventual death to God in prayer. It doesn’t matter how we do it as much as that we do it. One method I include in all my books is The Memento Mori Daily Examen. Based on a method of prayer promoted by a 16th-century Spanish saint, Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the examen helps us to offer God praise and gratitude, identify areas of weakness where we need God’s help, and to ask for grace for the future. My version revises the prayer slightly to include a step in which a person explicitly can bring death to mind and pray with it in the context of faith.

Sr. Theresa Aletheia Noble, FSP.

Salyer: I want to circle back to the relationship you mentioned between prayer and thoughtfulness. It strikes me that there’s a lot of overlap between someone like St. Augustine, for example, and the Stoics. Apart from Stoicism, which seems to be having a revival, are there any places where you see a devotional sense of memento mori reflected in popular culture?

Sr. Theresa: Among all the pop-culture references to memento mori, the Stoic reference has possibly the most affinity to the Christian meaning of the term. No doubt much of what Augustine wrote was indebted to Stoic thought. I love Seneca’s letters in particular; some of his lines are very similar to Augustine’s thoughts on the importance of keeping death in mind. What Christianity adds to the Stoic worldview is a more personalized view of divine fate or fortune. Amidst our failings, sins, and inability to live perfect virtue, grace abounds. God’s grace provides us with an ability to live even more virtuously than perhaps the Stoics thought possible.

Other pop-culture references to memento mori are usually closer to its counterbalance, nunc est bibendum (‘now is the time for drinking’) or the modern version, YOLO, ‘you only live once.’ This approach to life is far from the traditional sense of memento mori. It’s rooted in the idea that life is ultimately meaningless. I’ve seen modern Stoics and Christians alike confuse memento mori with this, but memento mori is anything but a call to nihilism or hedonism. Memento mori is about living our lives thoughtfully, intentionally, and with purpose—with God at the center.

Pope Francis (L) delivers an address from Rome's City Hall by an equestrian statue of Marcus ... [+]

Salyer: ‘Living intentionally’ – The New York Times mentioned that you grew up listening to The Dead Kennedys and going to punk shows. That idea of living intentionality always drew me to punk growing up – wanting to not be lied to, wanting a sense of justice. In your experience, have you found that anything translates between a punk ethos and the charism of religious life?

Sr. Theresa: I’ve noticed that sometimes when people have conversion experiences, they tend to refer to their past in a derogatory way that diminishes how God was working in their lives. People expect me to speak of punk music and my past with shame and regret. But in many ways the punk rock saved me when I was growing up in Oklahoma. I was struggling with the problem of suffering and that music, and the other people attracted to that subculture, gave me the space to struggle, to desire justice, to be angry, and to ask questions.

It’s taken me some time to resolve where I was then with where I am now, but I’ve realized that there’s a natural affinity between the two. I’m still angry about the problem of suffering. But my rebellion against the problem of suffering is now lived out in my rebellion against sin. I trust that God is doing something deeply good in the world through my dedication to his way of life—poor, chaste, and obedient. Punk rock is rebellious, but religious life is the ultimate rebellion.

Sr. Theresa Aletheia Noble, FSP

Salyer: If I die before I finish writing this article, what’s something essential you would have wished that I’d asked you?

Sr. Theresa: You very well could die before finishing this article! And I before the article is published! We all know someone who has died without warning, without saying goodbye. That’s why memento mori is so important, regardless of one’s religious beliefs.

We begin to die the moment we are born, and a good life is lived in accepting that context, not in its denial. Thus, one of the most important questions we can ask ourselves is, ‘am I going to live my life avoiding death or preparing for it?’ I would have wished that you had asked why it’s important to do that in the little time you had left.

The Chapel of Bones, Capela dos Ossos, city of Evora, Alto Alentejo, Portugal, southern Europe. ... [+]

You can follow Sister Theresa on Twitter and Instagram, and find the Memento Mori project here. Her essays appear regularly and she is the author of The Prodigal You Love, Remember Your Death: Memento Mori Lenten Devotional, and Remember Your Death: Memento Mori Journal.