Members of a court in France prepare for trial.

It’s a bewildering time for oil and gas companies in the US. First, many are still basking in the success of the shale revolution, which took place in the past 20 years, and after which the US became self-sufficient in oil and gas for the first time since 1947.

Since President Biden has come to power, climate change has been labelled an existential crisis and been elevated in government to cabinet status. The implication is that oil and gas production, which contributes over 50% of greenhouse gases (GHG), has to cut back and make room for rapidly increasing renewable energies.

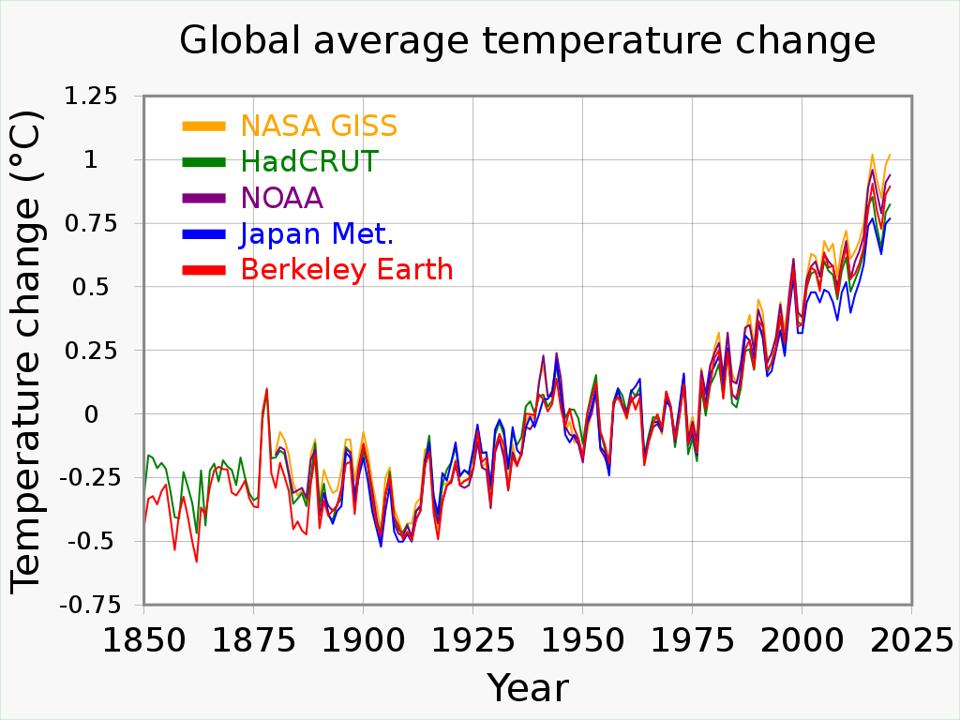

Many US oil and gas companies have adopted a “wait-and-see” attitude. Yes, physical evidence for climate change is clear - such as retreating glaciers, Arctic ice melting, and corals bleaching. The temperature increase behind these is indisputable (Figure 1). The increase in recent decades is dramatic with no sign of flattening the curve.

Figure 1. Global mean surface temperature from several observatories.

But there exist opposing data, which stopped at 2016, that show the direct effect of climate change on humanity has not worsened in the last 50 years. This global data includes intensity and frequency of droughts, wildfires, tropical storms, and hurricanes (Ref. 1).

While many US companies are content to wait, European counterparts are not. EU companies are responding to political pressure (after all they had no shale gas revolution), to stockholder pressure, and to populace pressure. These may be called external pressures to distinguish them from internal company motivations to change.

· Bp has committed to 40% renewables by 2030 and is likely to succeed in a bid for a world-class UK offshore wind farm in the Irish Sea. BP studies are aimed at building the largest blue hydrogen plant at Teesside in the UK. By 2030 this will provide 20% of UK’s production that will be used in transportation.

· By 2021, Shell in Germany will provide 10 MW of green hydrogen. In Ireland, they will be a 51% stakeholder in a 300 MW wind farm.

· Total, since 2016, have invested $8 billion in renewables. An example is a $2.5 billion buy-in of Adani Green Energy which includes a 50% partnership in their solar energy company.

Court pressure on Royal Dutch Shell.

This week oil giant Shell was ordered to cut their GHG emissions quicker than planned: by 45% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels. Essentially this would mean cutting GHG emissions by almost half in the next 10 years.

An environmental group, Friends of the Earth, plus six other entities and 17,000 personal signatories, in 2018 sued and requested the Dutch court to order Shell to bring their GHG emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Shell’s defense rested on current laws which they were complying with, and that the company was at the forefront in addressing climate change by pledging to have net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, and by limiting methane emissions from all parts of their upstream and downstream supply chain.

The company said it is already “investing billions of dollars in low-carbon energy, including electric vehicle charging, hydrogen, renewables and biofuels. We want to grow demand for these products and scale up our new energy businesses even more quickly.”

Shell argued that if a new law about GHG emissions were to be applied it needed to come from policy changes and incentives via the Dutch government. Instead, the Dutch court ruled that Shell must abide by the Paris Agreement of 2016 as well as Dutch law.

The picture of the judges filing back to the courtroom did not reveal the insightful minds behind the black robes. The court ruled that Shell’s policy “is not concrete, has many caveats and is based on monitoring social developments rather than the company’s own responsibility for achieving a CO2 reduction.”

“Therefore, the court has ordered RDS [Royal Dutch Shell] to reduce the emissions of the Shell group, its suppliers and its customers by net 45%, as compared to 2019 levels, by the end of 2030, through the corporate policy of the Shell group.”

This is meaningful phrasing - less monitoring of social developments and more specific responsibility for reducing GHG emissions – directed at a company that is amongst the oil and gas company leaders in addressing climate change.

Shell must also assist their suppliers and customers in reducing their own GHG emissions. Suppliers could be service companies who carry out fracking operations, for example, and this might require them to use renewable electricity to power their frac pumps.

Customers, in its broadest sense, could include businesses or people that buy gasoline from Shell for their cars, or natural gas to heat their premises - because gasoline and natural gas burn to carbon dioxide (CO2) which is the gas that causes most of the global warming.

The words “Suppliers and customers” shift Shell’s responsibility to a much higher level than just making their own operations carbon-free. One reason is Shell’s products are forms of oil and gas which will be burned to CO2. This is a fundamental dilemma for all oil and gas companies simply because they produce oil and gas to be burned, and the Dutch court has come down hard on Shell over this issue.

Shell will likely appeal the court’s decision.

The bottom line, at least in the Netherlands, is that Shell has to comply with the Paris Agreement as well as local GHG emission laws. If this ruling stands as precedent it may have far-reaching implications for civil lawsuits in other countries, and for an oil and gas industry that is already wrestling with other external pressures.

Ref. 1. Gregory Wrightstone, Inconvenient Facts, Silver Crown Productions, 2017.