Marks & Spencer announce companies full year results, an 88% slump in full year profit. The 137 year ... [+]

There seems to have been a revolving door in and out of the Marks & Spencer board room for two decades, and yet still the bleak financial figures continue to show for it.

In today’s announcement of the company’s full year results, the 137-year old retailer reports an 88% slump in full year profit and blames the pandemic and forced closures of stores for severely constraining the store network. It has announced there will be further store closures.

Once again shareholders have to face the facts that clothing and home sales have dropped, whilst food operations have seen an improvement in a period when all the large grocery brands have seen sales growth driven by the demand from consumers forced to stay at home.

Whilst Marks & Spencer claims the balance sheet is stronger than expected, many will want to know why Marks & Spencer’s turnaround plan is still not showing signs of take-off.

The last time the company hit record pre-tax profits of £1.2 billion was in 1998 and the business was flying high. Core messaging was centred on the quality, value and service

The business has been floundering for decades, and whilst under Chairman Archie Norman’s (ex ASDA) watch, there may be a more realistic survival strategy, the gap between what customers want and what the brand delivers seems to be still distant.

Whilst Norman seems focused on bringing back a clear and reliable offer, centred around value - critical for the foundation of the brand for core customers, efforts also seem to be immersed in imitating the likes of Next, a brand which has seen investment in its digital operations and the selling of other brands. Marks & Spencer announced it would start to sell rival brands such as Phase Eight, Seasalt Cornwall and the Early Learning Centre, in a hope to “turbocharge” online sales.

The question is, is there enough consumer appetite for another Next? The fashion retailer had success from building on its Next Directory customer base, for which it has offered credit facilities for account holders, transforming it into a slick and quick delivery offer. The focus has been to develop faster, more personalised and smarter solutions for customers for many years offering a significant directory of brands for all price points. Speed of delivery and return and appealing beyond the core customer base into different age demographics has also contributed to the retailer’s success.

Lord Wolfson, Chief Executive of Next is considered a wise, rational voice when it comes to retail matters, cemented by the management of the brand during the crisis which has seen competitors such as Arcadia and Debenhams crumble and fail.

At a time when demand for home furnishings, casual clothing and of course children’s wear, due to many children needing a 7-days-a-week wardrobe when school uniform became obsolete, Next was ready to serve.

Next took the opportunity to take a 25% stake in clothing brand Reiss, and further invest in technology.

Wolfson predicted profits hit by the pandemic would fall below £100million, but reported a better-than-expected result of profits at £342 million after a solid performance at Christmas.

Next delivers resiliently well in the middle market, and it is the success of Next, and also brands like Zara, Primark, e-tailers brands such as ASOS, and supermarket’s own brand clothing offers such as TU (Sainsburys) and Nutmeg (Morrisons) that has created a much more diverse offer for customers who just want so much more than Marks & Spencer can currently offer.

There could not have been a blunter raison d’être in Steve Rowe’s “Never The Same Again’ programme - the business had to change radically.

In August 2020, the business announced it would make 7000 job cuts, and shortly afterwards, it announced its first loss in 94 years. It was relegated from the FTSE 100 in 2019 after 35 years, and has been on a store closure programme since 2016.

Competitor John Lewis Partnership also endured a torrid time, with Chair of the Partnership, Dame Sharon White describing 2020/21 as “the most challenging in the Partnership’s history” as the business recorded a Loss before tax of £517 million (compared to a Profit before tax of £146 million in the previous year) in results.

Both organisations have been accused of not moving with the times and evolving the business apace with the changing retail environment.

Marks & Spencer CEO Steve Rowe’s plan is to streamline and improve the clothing range, open larger food halls with a fuller range and of course cut costs where possible. Last week the Chief Executive was quoted to say he has “fixed the basics” and the pandemic has helped to accelerate the transformation plan.

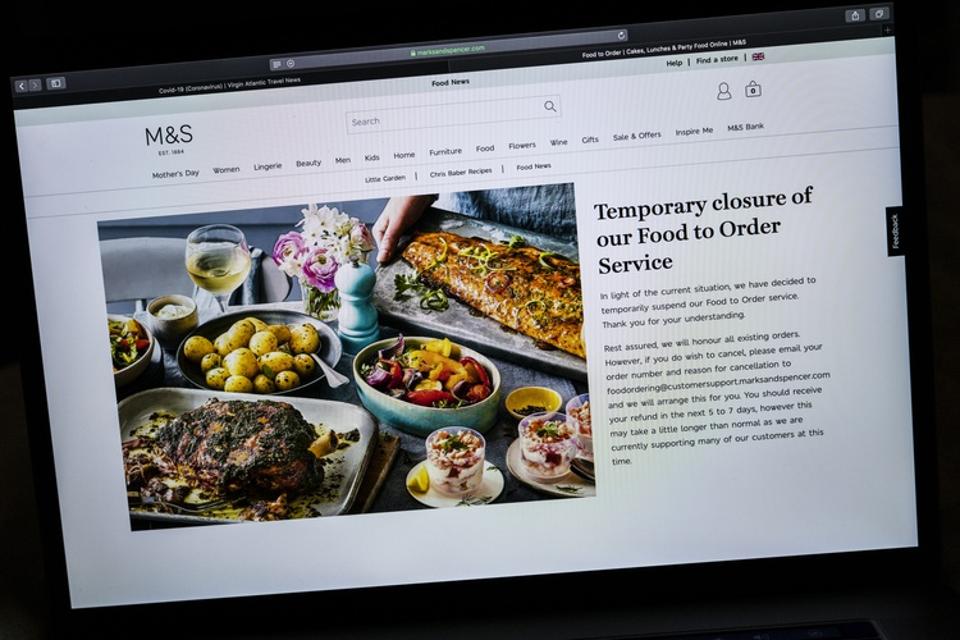

The business partnered with Ocado to start a grocery home delivery service for the brand, and the partnership contributed a share of net income of £78.4m “in an exceptional period for the business and following the successful switchover to M&S supply.” The chain plans to “aggressively grow capacity” in the venture.

The market seems to demonstrate a faith in the changes, with shares up 14% since the start of the year.

But the absolute truth will lies with the consumer’s belief and spend, whether they trust or even want Rowe’s vision of a “curated set of brands and merchandise” or feel completely content in their own capacity to curate their own online experience, as a more confident and savvy shopper, will soon be understood.