Isabella Casillas Guzman attends a Senate Small Business and Entrepreneurship hearing to consider ... [+]

If we were to do free association with the phrases “federal procurement” or “government contracting,” chances are most people would say things like “bureaucracy” or “paperwork.” Words like “vitality” or “resilience” probably wouldn’t be top of mind. That’s not unfair: working as a government supplier can be slow and full of frustration.

Yet procurement is economically important—and, it’s a key way by which government interacts with small businesses and entrepreneurs. In turn, small businesses contribute to resilient supply chains and industrial base vitality. Reforms are needed, however. We need to ensure that small businesses continue to want to work as federal contractors. And, we must make procurement processes less cumbersome and more transparent.

Big Business for Small Firms

In an interview last week with Axios Re:Cap, Small Business Administrator Isabel Guzman highlighted contracting as one of her four top priorities. “We want to make sure that we connect our small businesses to available contracts,” she said, “and so that focus is going to continue.”

Federal contracting—government purchasing of goods and services—is big business. In fiscal year 2019, according to the Government Accountability Office, the federal government chalked up $586 billion dollars in procurement obligations. For context, that’s slightly larger than the entire economy of Sweden.

Each year, 23% of federal procurement spending must go to small businesses. That’s tens of billions of dollars going to small American companies. The 23% goal has been achieved seven years in row, and the average over that time period has been closer to one-quarter. (Of course, for the seven years before that, the government failed to reach the 23% goal.) For fiscal year 2019, the SBA awarded the government an “A” grade. Yet the top-line goal masks considerable variation as well as some trends that are not-so-great for small businesses.

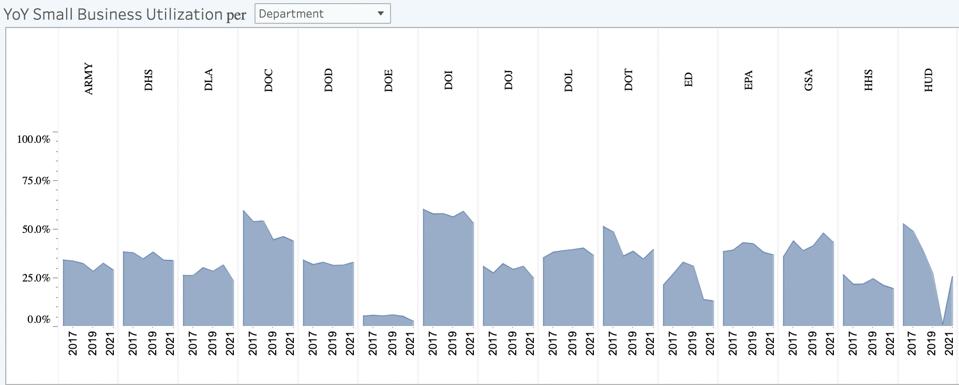

Small business share of federal procurement spending, by agency.

As the chart above shows, some federal agencies and departments meet or exceed small business spending goals each year. Others do not, but this variation reflects differences in industries and their business composition. Small businesses are more prevalent in the construction and maintenance sectors, for example.

More worrying for small business advocates is that the number of small businesses providing common products and services to the federal government declined by 38% from 2010 to 2019. The government is meeting its 23% goal, but with a shrinking pool of small businesses. Part of that decline represents fewer small businesses even trying to break into the federal procurement marketplace. A 2018 analysis by the Center for Strategic and International Studies found a startling 72% drop in the number of new small business entrants into federal contracting between 2005 and 2016. Many small businesses, it appears, just say “no thanks” to participating in procurement.

“Do They Really Know What They’re Asking?”

Small business owners who do contract with the government are not surprised by those findings. Over the past several weeks, the Bipartisan Policy Center—together with the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses Voices program and Center Forward—has been talking to small business contractors.

A word cloud of those conversations would prominently feature “cumbersome,” “time consuming,” and “expensive.” It’s “so complex,” said one small business CEO, “to understand what you need to do, how to find opportunities.”

Despite dedicated efforts to include small businesses in federal procurement—such as the 23% goal—many feel like the deck is stacked against them. “We do get scrutinized much more closely than a larger business,” one business owner told us.

What Might Be Done

For some observers, this may not matter much. One knock against small businesses is that they can’t handle scale and efficiency as well as larger companies. I’ve heard some say that the onus is on small businesses to “up their game” if they want a bigger role in public procurement.

Perhaps, but efficiency is just one public priority and must be balanced against others. The Biden administration, in executive orders and its recent budget proposal, has recognized that small businesses play a key role in “secure supply chains.” Three years ago, former Defense Secretary James Mattis pointed out that a “secure national security innovation base” depends on welcoming “new entrants and small-scale vendors” into procurement.

How might small businesses and entrepreneurs be better recruited and included in the federal contracting marketplace?

For starters, the top-line goal of 23% could be raised. It’s been unchanged since 1997. Specific goals could also be established for new entrants. Both of these imply concerted efforts to make processes of certification and bidding as smooth and efficient and, yes, inviting as possible.

More resources could also be allocated to SBA for monitoring and enforcement. Few politicians, of any stripe, would go to the mat for greater funding for compliance. But taxpayers would be better-served if resources were increased for reducing fraud and increasing small business participation.

Making improvements to data collection and tracking would also be a high-leverage way to change overall procurement. The system for gathering data on prime contractors’ use of small business subcontractors, for example, is in particular need of greater robustness.

Procurement reform doesn’t top a lot of elected officials’ priority lists. It doesn’t get featured in campaign ads. But federal contracting is a big part of the economy; small businesses play an important role as suppliers. In doing so, they strengthen supply chains and regional economies. Expanding their participation should be a shared political priority.