When the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“TCJA”) was passed in December 2017, many residents on the east and west coast felt like they heard fingernails scrapping against a chalkboard. It officially become federal law that the maximum amount of state and local taxes (“SALT”) that could be included as a federal itemized deduction, and thereby decrease federal taxable income, was limited to $10,000 regardless of filing status. For many individuals the state income tax withheld plus the high real estate taxes often paid on the coasts, greatly exceeded the maximum deduction of $10,000. The federal offset of saving $1 of federal taxable income for a $1 of SALT paid was severely restricted.

SALT Cap on Federal Deduction

States have been grappling ever since on how to ensure that state and local income taxes could be deducted in full on their federal tax return, trying to identify a way to work around the SALT $10,000 cap. The federal courts were quick to dismiss a case brought by four states, including New York, to the federal district court arguing that the new $10,000 federal SALT limit under the TCJA meaningfully impaired their ability to pursue their own preferred tax policies. Other state agencies, again including New York, tried to develop charitable funds where individuals could make a charitable donation to the local charitable fund and then offset their real estate taxes due for the charitable donation made. This was an attempt by the state agencies to reclass the real estate tax expense from a federal SALT deduction (which would be limited) to a charitable deduction (with a much larger limitation) and therefore allowing for a larger federal deduction. The Internal Revenue Service was quick to issue regulations denying this work around as well.

But at last, the IRS opened a window for a SALT work-around on November 9, 2020 by issuing Notice 2020-75 which allows for an amount paid by a partnership or an S Corporation to a state (or subdivision thereof) to satisfy its income tax liability, to be deductible in computing the entity’s federal taxable income, and that such payments are not taken into account in applying the SALT cap to any partner or shareholder of such an entity. The New York State legislature and the governor included this SALT workaround in the most recently approved budget that was passed on April 6, 2021. Other states that have passed similar legislation include Connecticut, Louisiana, Maryland, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and Wisconsin.

The Pass-Through Entity tax allows an eligible partnership or S Corporation to make an annual election to pay the New York State tax at the entity level and the direct individual partner or shareholder of the electing entity will be allowed a credit against the income tax imposed on their New York return. So, let’s answer some general questions surrounding the election.

1. When does an eligible S Corporation or partnership have to make the election to pay the pass-through entity tax?

In general, the annual election must be made by the due date of the first estimated payment and will take effect for the current taxable year. The election is irrevocable for the year in which it is made. Therefore, if a pass—through entity wants to make an election for 2022, it must be made by March 15, 2022.

There is an exception regarding the 2021 taxable year. The election to pay the pass-through entity tax is not required to be made until October 15, 2021. For 2021 only, the electing partnership or S Corporation is not required to make estimated tax payments for the 2021 taxable year. Partners and shareholders of a 2021 electing partnership or S Corporation must continue to make estimated tax payments as if they were not entitled to a tax credit.

We are still awaiting guidance from New York State regarding the ability for a pass-through entity to make a 2021 election even though the direct partners and shareholders are required to continue making 2021 estimated tax payments. Guidance is needed on how the estimated tax payments will be captured as a federal deduction on the electing partnership or S Corporation tax return if the entity itself is not paying the tax. Alternatively, and probably more likely, New York State may be looking for both the direct partners and S Corporate shareholders to pay estimated tax payments in 2021 AND the eligible pass-through entity to pay the tax again when making the election on October 15th. Essentially allowing New York State to get paid twice, and float the overpayment until tax returns are filed with refund requests.

2. Who can make the election for the pass-through entity?

In order for the annual election to be effective, it must be made by an officer, manager or shareholder of an S Corporation who is authorized under the S Corporation’s organizational documents to make the election and who represents under penalty of perjury that they have such authorization. If the entity is not an S Corporation, any member, partner, owner or other individual with authority to bind the entity or sign returns can make the election.

3. If the election is made, how does the electing S Corporation or Partnership calculate the estimated tax due?

Step 1: The first step is to identify the sum of all items of income, gain, or loss or deduction to the extent they are included in the New York State taxable income of a nonresident or resident partner, or to the extent they would be included in New York State taxable income of a S Corporation shareholder.

It is important to highlight if you are an S Corporation shareholder the amount of income that you are allowed to filter through the Pass Through Entity Tax (based on the wording of the law) is ONLY the amount of taxable income sourced to New York State, even though for New York State residents the total amount of taxable income form the S Corporation will be taxed on the New York State individual income tax return. Yes, you read that correctly! New York taxes an individual’s worldwide income if the individual is deemed a resident of the State. Therefore, if an S Corporation sources all their income outside of New York state, and the owner is a New York resident, they will not be able to elect to pay New York state income tax at the S Corporation level even though the entire amount of income is taxed in New York State. Seems ridiculous? I agree. We can only hope that further clarification is provided by New York State to address this issue.

Step 2: The estimated tax payment is calculated using New York taxable income under Step 1. The electing entity is only required to pay the lesser of the below amounts in four equal installments:

· 90% of the current year tax or

· 110% of the tax shown on the return of the electing partnership or S Corporation for the previous taxable year (suggesting if there is no previous tax year for the electing partnership or S Corporation tax return they must base their estimated tax payments off current year projections)

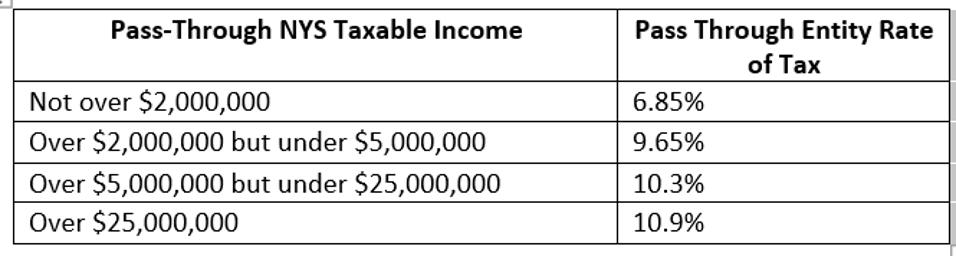

The tax rate that will apply to the estimated taxable income is based on the electing partnership or S Corporations taxable income:

New York State Pass Through Entity Tax Rate

The four equal installments are due on March 15th, June 15th, September 15th and December 15thof the current taxable year.

To further understand how the mechanics work, lets walk through a simple example.

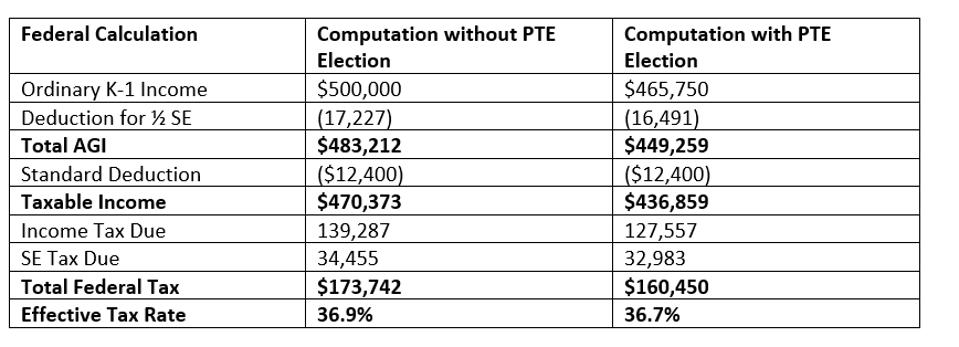

Assume Partnership Y, a New York State partnership, has three partners; Lynn, Jen, and Tammy who are all New York State residents. The partnership interest is owned equally, and the taxable income is also allocated equally. Partnership Y decides to make the pass-through entity tax election and pay the 2022 New York State tax directly. Partnership Y ‘s ordinary taxable income is $1,500,000 before any New York State income tax payment. When Partnership Y makes the pass-through tax election, it is required to pay New York State tax in four equal installments for a total amount of $102,750 (1,500,000 x 6.85%). For federal income tax purposes, the amount of ordinary income allocated to each partner would have been $500,000 each (1,500,000/3) if no election was made. However, as the Partnership made the pass through entity tax election, the amount of ordinary income that is now allocated to each partners federal individual income tax return decreases to $465,750 (1,500,000-102,750)/3)). As the partnership paid the tax and the adjustment is included in the income that flow to the partners, the partners are not required to report the tax paid as a SALT for purposes of the itemized deduction and the limitation of $10,000 does not apply. In addition, if the income provided by the partnership is subject to self-employment tax, the partners are able to see a reduced amount of self-employment tax.

Federal Calculation with and without PTE Election

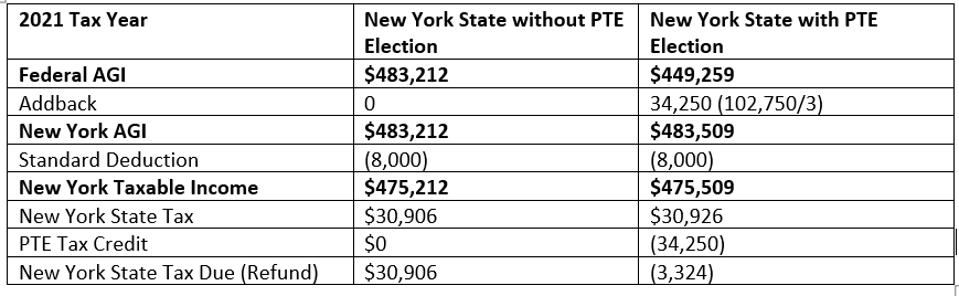

For New York State individual income tax purposes, the amount of tax paid by the partnership allocated to each partner would be a New York State addback. Assuming no other addbacks are required, each partner would report New York State taxable income of $500,000 and then report a credit of $34,250 each (102,750/3).

New York State Calculation with and without PTE Election

While many pass-through entities see the benefits of the New York State pass-through entity tax election, it does become more complicated when you have non-resident partners or income that is not sourced to New York. In addition, the administrative oversight can be overwhelming as well. For example, how will electing partnerships or S Corporations collect the tax to pay New York State estimated tax payments? Will the estimated tax payment amounts be reduced from partner draws or withheld on the compensation paid to S Corporate shareholders? In addition, what partnership agreement or incorporation document adjustments does such an arrangement require?

In addition, the tax rate that could apply to partnerships or S Corporations that make a pass-through entity election could be much higher than the New York State income tax rate that the individual S Corporate shareholders or partners currently apply. If some type of withholding is required by the electing entity, will partners or S Corporate shareholders be open to a potential larger withholding amount through the year when if the individual partner or S Corporate shareholder paid the estimate income tax payments individually the cash outflow could be lower.

While the benefits and hurdles are still being debated, and professionals are patiently waiting for additional New York State guidance, I think many will agree that they are greatly relieved to find a potential work around solution to avoid the federal limitation of only being able to deduct a maximum amount of $10,000 of state and local tax. After all, with the ever-increasing New York State income tax rates there has to be some enticement to keep businesses around.