Sad adult woman sitting on dark home corridor floor.

In the face of unprecedented levels of anxiety and depression, the Covid-19 pandemic has been good for at least one thing: reducing traditional taboos about mental health.

Yet even as the importance of mental health care may never have been more clear, a majority have not sought treatment, according to a recent survey by researchers at Edith Cowan University in Perth, Western Australia.

More than half (54%) of the survey’s 1,008 respondents across the U.S., Europe, and Australia rated their mental health as fair or poor. Nearly half (44%) reported that their mental health had declined since the onset of the pandemic, with women (48%) and Millennials (45%) most likely to report negative mental health effects.

Despite experiencing mental health issues, 55% reported not seeking mental health treatment, including 39% of those who reported that their mental health status was poor.

Nearly one in five (18%) said addressing their mental health was a top priority, but still only 44% of people in this group were seeking professional mental health services.

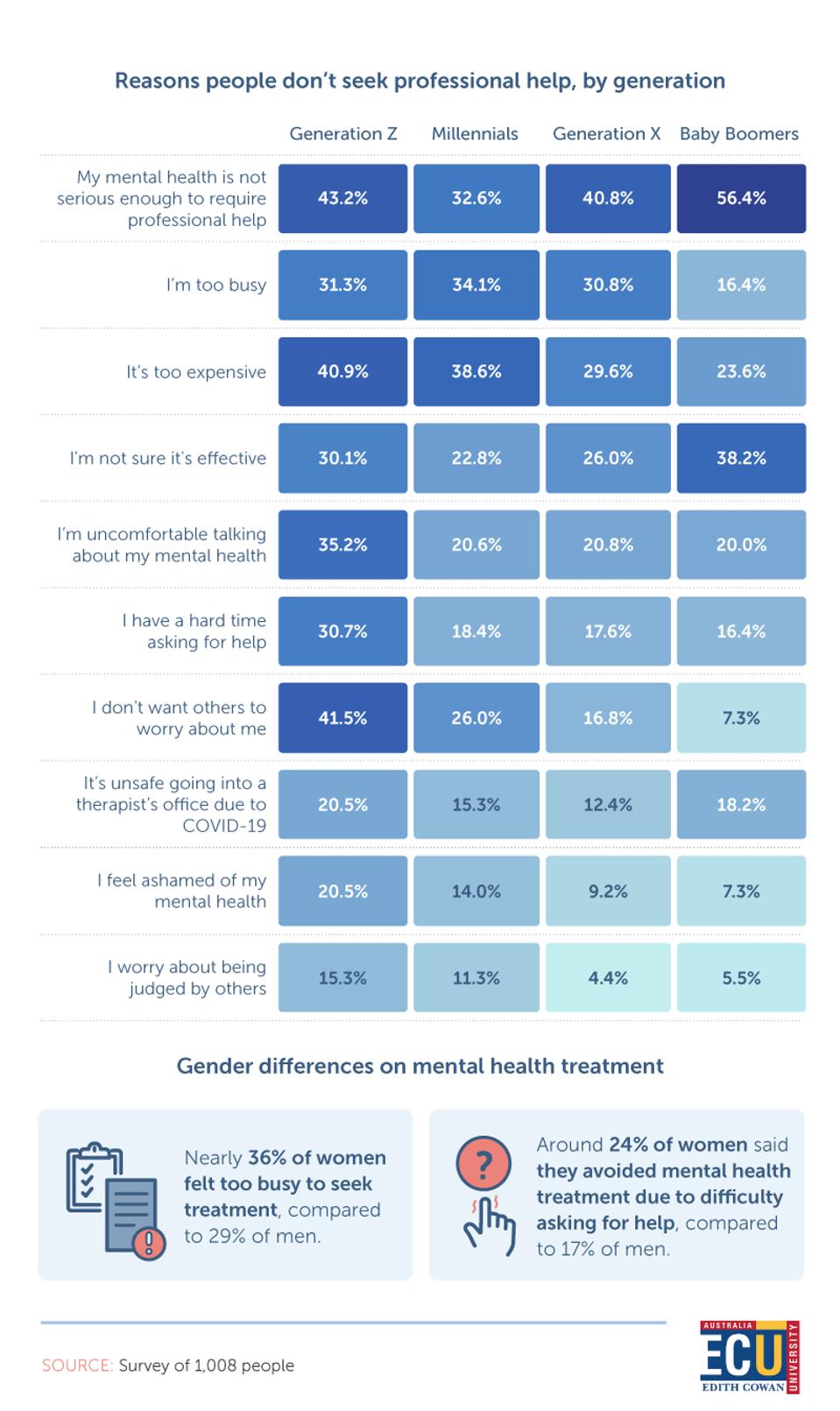

Thirty-eight percent of respondents said they didn’t seek mental health treatment because they didn’t think that their mental health issues were not serious enough to do so. This sentiment was most common among Baby Boomers (56%) and Gen Z respondents (43%).

The second most common obstacle to seeking professional help was cost. Overall, 36% of survey respondents—including 41% of Gen Z respondents—said mental health treatment is too expensive.

Nearly one-third (32%) of respondents said they were too busy to seek treatment, a response disproportionately cited by women (36%) compared to men (29%). Women also reported more reluctance to ask for help (24%) as a reason for avoiding professional mental health help, compared to men (17%).

Reasons people don't seek professional help, by generation

Whatever the reason, respondents who did not seek help were more likely to report negative impacts on their social lives, their energy, and their motivation at work. People who ignored their mental health issues were four times more likely to report that their mental health affected their willingness to eat healthily. They were also more than five times more likely to report an impact on their willingness to exercise than people who were seeking treatment.

Melody Kasulis, project manager at Edith Cowan University, explained the impetus to run the survey.

“We wanted to see just how much of a toll the pandemic had taken on our mental health,” Kasulis said. “With the loss of many jobs also came the loss of health benefits, which we found negatively impacted the mental health of over 37% of those impacted.”

Of the 21% of respondents who’d been affected by lost income due to the pandemic, 42% of women said that salary cuts had negatively impacted their mental health compared with 28% of men. Women were also twice as likely as men—14% of women versus 6% of men—to report negative mental health impacts from children being home for remote schooling.

Researchers did not publish comparisons between respondents in different countries, but studies from the U.S. and Australia show elevated rates of depression and anxiety during the pandemic, despite very different Covid-19 infection and mortality rates.

Globally, the estimated rate of depression during the pandemic (25%) is seven times higher than pre-pandemic levels (less than 4%).

Access to mental health care may vary in these countries but the needs appear to be universal.