Differences in LIBOR replacement rates could create anomalies for some complex deal structures.

Floating rate debt instruments for commercial real estate loans and many other forms of financing have for decades relied on an interest rate index called the London Interbank Offered Rate. If LIBOR went up or down, so would the interest rate a borrower paid. And LIBOR rates were quoted every business day for a range of borrowing periods, from one day to a year. In real estate, the most common borrowing period has traditionally been 30 days, so real estate LIBOR loans are repriced every 30 days.

About a decade ago, it became clear that LIBOR partly reflected creative writing by money traders at major banks. It did not reliably or precisely reflect actual market conditions for borrowing and lending. So the regulators and industry organizations decided LIBOR was broken, and the market should move away to something better.

Hence began a multi-year and surprisingly complex exercise. So far, its main conclusion has consisted of a suggestion to replace LIBOR, at least in the United States, with something called the Secured Overnight Financing Rate. SOFR fluctuates daily and is determined after the fact (in arrears) rather than at the beginning of each borrowing period, which is always just one day. In contrast, LIBOR pricing is set at the beginning of each borrowing period. And it offers a range of possible borrowing periods of up to a year. SOFR also assumes an absolutely risk-free borrowing rate at all times, so will not respond to changes in the pricing of money driven by changes in overall credit risk in the financial markets as a whole. Based on those differences alone, the suitability of SOFR as a replacement for LIBOR hardly seems obvious.

The international bank regulators have in recent months beaten their drums more loudly to announce the upcoming demise of LIBOR, but the SOFR substitute has achieved only limited traction. More promisingly, private players have come up with possible replacements for LIBOR: the Ameribor rate promulgated by the American Financial Exchange; the Short Term Bank Yield Index from Bloomberg (BSBY); and the Bank Yield Index from IBA.

Possible replacements for the LIBOR interest rate index could create surprises for deal structures ... [+]

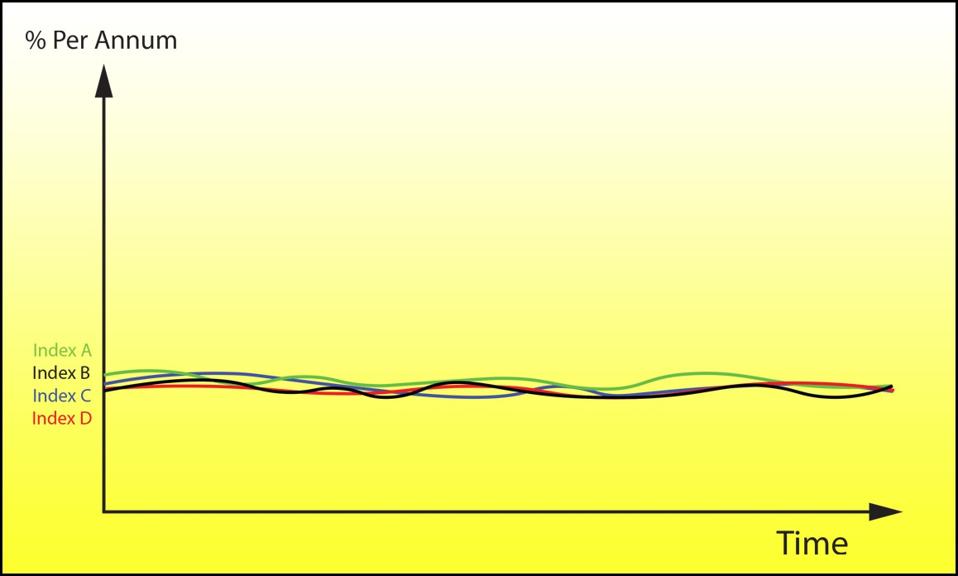

Unlike the SOFR index, these three new possible replacements for LIBOR include a credit risk element, are quoted in advance, and offer a range of borrowing periods. They look much more like LIBOR. Regulators are generally open to these substitute rates, subject to some lingering concern about how they might behave over time and especially in times of stress.

Market players should be smart enough to figure that all out, with or without help from the regulators. The market should, over time, get comfortable with one or more of these substitutes for LIBOR or with some other privately created replacement index.

That creates a new problem. Some long-term financial structures with LIBOR-based interest rates involve two different sets of documents and relationships. Each set has its own language to deal with the possibility, once purely hypothetical, that LIBOR might go away. For example, floating rate residential mortgage loans have a mechanism to replace LIBOR if it goes away. Many of those residential loans generate mortgage payments that, in turn, fund payments to the holders of bonds. But those bonds often have a different mechanism to replace LIBOR if it goes away.

Those differences will create some disconnect between the stream of incoming cash and the outgoing payments that the same cash flow needs to fund. One LIBOR replacement rate might move differently from another. The result: a risk or perhaps a pleasant surprise for the institutions that make the outgoing payments to the bondholders. This disconnect also may create an opportunity for whoever gets to decide on each replacement for LIBOR. The result could be litigation, unexpected profits or losses, and perhaps a new product for the derivatives industry.

Identifying the problems with LIBOR was perhaps relatively easy. Figuring out the ideal replacement for LIBOR turns out not to be so easy.