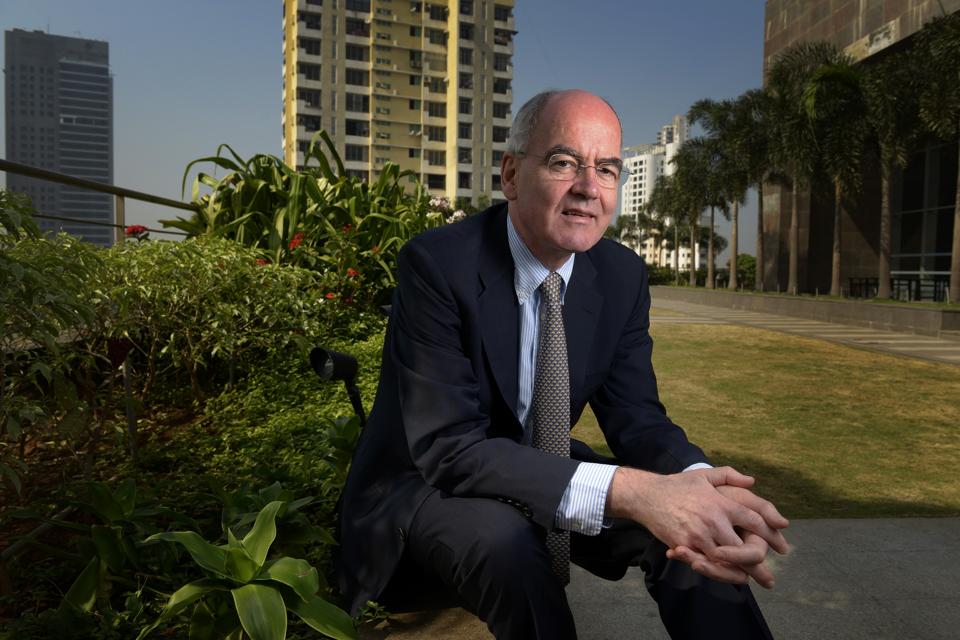

John Elkington, the Volans founder, is optimistic that business is getting serious about ... [+]

In many ways, this is a great moment to be in the consultancy and advisory business. The pandemic has quite literally turned conventional thinking on its head. As The Economist newspaper recently reported: “Think-tanks that churned out papers on slimming the state under David Cameron, prime minister from 2010 to 2016, now bristle with ideas for how to toughen it up.” Governments — such as that in the U.K. — normally associated with tight spending controls have loosened the purse strings in a way not even seen in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 in a desperate attempt to keep the world economy afloat in the face of a devastating virus. In the words of John Elkington, the sustainable capitalism pioneer, “it unsettled people enough” to make them want to look at doing things differently.

Of course, the large multinational firms, such as McKinsey & Co and the consultancy arms of the large accountancy practices, are offering all sorts of expertise from supply chain management to the introduction of new working practices in response to the unfamiliar environment created by the global health crisis. But Elkington, while professing that he is not against these large players, feels there is also a need for advisers to provide something more challenging to boards that might feel that incremental solutions are going to be enough.

He co-founded Volans in 2008 with the aim, according to the organization’s website, of striving to “span the yawning divide between current approaches to sustainability and what’s needed to create a truly sustainable future for all. Inspired by the flying fish, Piscis volans, and other creatures with the surprising gift of flight, our aim is to make great leaps in progress, achieving breakthrough change.” More than a decade later, the team remains determinedly small yet seeks to create big repercussions through working across big business, innovators, the public sector and non-governmental organisations.

Louise Kjellerup Roper, who joined as CEO a little over three years ago after extensive experience as an executive with environmentally-focused brands, believes that the pandemic (and the even bigger issue of climate change) are forcing companies to acknowledge that they will not be able to go back to doing things as they did them before. They have to accept that there is uncertainty ahead, she says, pointing out that back in November 2019 Volans produced a report for a client that listed as the number one threat — a pandemic. Other threats included a financial crisis and armed conflict. Both she and Elkington stress that such threats are often integrated and create a sort of domino effect.

Looked at this way, it appears rather inevitable that — with concern over global supply chains leading to increasing economic nationalism — a container ship should block the Suez Canal. The key, according to Elkington and Roper, is not to respond incrementally by, in this case, widening and depending the canal and thereby making it possible for even larger ships to use it — and potentially block it again. Instead, organizations need to “become more alert to weak signals” that, taken together, can indicate something significant is happening.

After spending decades encouraging businesses and their investors to think beyond pure profit with mixed results, Elkington remains optimistic. “There is growing enthusiasm for really getting on top of this [climate change],” he says. Executives are “really thinking about what it means for their business.” Moreover, he sees much to cheer in such developments as Blackrock CEO Larry Fink’s annual letter to shareholders encouraging them to think about sustainable growth, institutional investors’ increasing commitment to ESG (environmental, social, governance) principles and the fact that the sustainability function is becoming more associated with finance within businesses.

He and Roper see a firm like Volans, which likes to act as a catalyst by working with a variety of partners, influencing this trend by helping bigger advisory firms to change the sort of advice they offer. But it is also offering practical demonstrations of what is possible through ambitious projects like the River Leven Programme, a regional regeneration partnership, led by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, that aims to transform an area that was once at the center of Scotland’s industrial revolution, through sustainable, inclusive growth. Created two years ago, the “sustainable growth agreement” saw an initial 11 public and private sector partners including Scottish Enterprise, Fife Council and global spirits manufacturer Diageo, as well as SEPA, working together in what is being seen as a pioneering way. A year ago, a further five partners joined. As Roper said at the time: “The alignment of environment and economic agencies with private partners to accelerate regeneration in Leven can be a model for Scotland’s green recovery.”