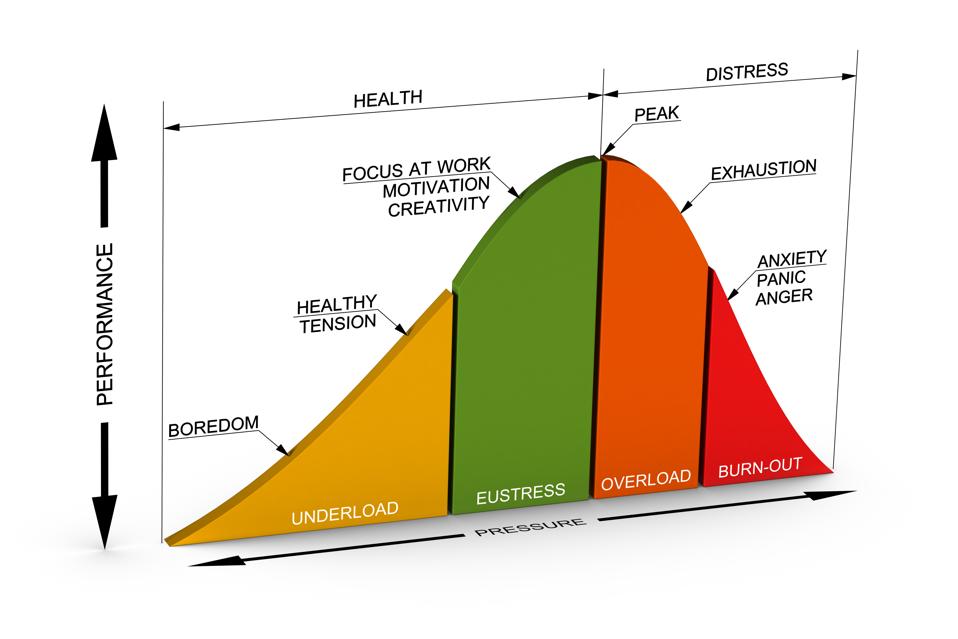

3D illustration of the different stages of stress curve over white background

The stereotype exists that disabled or neurominority people are not competent or high-level workers, that we are somehow inherently lazy or not able. In the US, for example, it is still legal to pay disabled workers a lower wage. In the UK we have problems with people who are medically unable to work being declared fit and told they must find a job, as if the only problem is their attitude.

Disabled people are over-represented in inspirational videos where someone is congratulated for a completing a relatively simple task, but underrepresented in the media where very few every day TV characters are disabled and those that are, are usually played by an abled actor.

So, with that information as a backdrop, I know many of my customers struggle to find the right balance between performance management, engaging ambition and providing an appropriate amount of support. This is tricky in most managerial relationships but has an added layer for marginalized people. Helping can be patronizing. Assuming incompetence is indirect discrimination. I know some managers worry about this a lot and want to do the right thing, so let’s discuss the difference between good and bad pressure.

Good Pressure And Bad Pressure

Did you know the relationship between stress and high performance is curvilinear? That means that as stress goes up, so does performance, until a max point is reached and then stress going up reduces performance. It’s called Inverted U Theory – the website Mind Tools has a good explanation and diagram to explain the phenomenon.

This is true for all staff, but in the neurominority community the edges can be more extreme. Many of us work best when under pressure, or when the stakes are high, and others can completely shut down with certain types of overwhelm. Some of us thrive when we are figuring things out and solving complex problems, but only if it is quiet! ADHD is often characterized by too little norepinephrine – a stress hormone – and when we don’t have enough we can’t concentrate. Put us under pressure and hey presto, we shine. However we are also more likely to be anxious and perfectionist, we have a higher prevalence of rejection-sensitive dysphoria and so how pressure is experienced can vary if the circumstances aren’t right.

Disability and neurodiversity are complex and no one person is the same, so if it feels difficult that’s because it is. But you can talk to your disabled colleagues about it. We are capable of adult-to-adult self reflection! You don’t need to take it upon yourself to “know best” what to do “for us.” Simply being aware that good and bad pressure affects us too, rather than assuming we need a nanny, and talking to us straight is a great place to start.

Focus On Strengths

Assuming competence and focusing in on what we can do rather than what we can’t creates the perfect jumping off point around which a framework of support can be built. Most disabled and neurodivergent people have good experience of overcoming difficulties and challenging themselves so we do not need or want to be protected. We do however like to know that if we have different processes, learning styles, social and environmental needs that our employer will understand and be inclusive.

To give a relatable example, I have a Dyspraxic team mate who finds learning new IT systems very overwhelming. She is competent but feels daunted and unsure. When she told me that she “wasn’t good with technology” I reminded her that she had helped to populate our website and had learned to use the back-end of a website relatively quickly with one short tech support session. The accommodation needed here wasn’t to have her avoid every project that involved learning new processes but instead to factor in the right preparation that would be needed to bring her up to speed. As a result of some “good pressure” she has built confidence and skills. She also has the sense of achievement that comes with confronting a challenging task. To have left her to do the work without guidance and an unmanageable deadline would have been “bad pressure.” To have excluded her from the project because of an assumed incompetence would have been simply unfair, this is the kind of "kid gloves" that prevent disabled employees from promotion and career acceleration.

Optimize Our Skills

The lesson in this for employers and managers is that a perspective shift is often needed when managing disabled and neurodivergent teams. Focusing too intensely on reasonable adjustments without also pushing people to grow professionally will result in a demotivated employee and also a lost opportunity to benefit from that persons’ skills. The alternative is not to abandon accommodations but to understand that they don’t mean a person is less capable. Allowing for difference means showing respect and understanding that different ways of doing things aren’t lesser. My dear colleague, Fiona Barrett (the token neurotypical in our leadership team) excels at this. She has a large and diverse team, and has excelled at bringing junior members of staff through to senior leadership. She's just won a "Rising Star Award" with the We Are The City network, founded by Vanessa Vallely OBE to support the pipeline of female leadership talent. People thrive under Fiona Barrett's leadership because she gives them opportunity and trusts them to succeed.

Assuming competence from day one is a must if you want to retain talented disabled employees, our abilities must be seen to reach their full potential.