HATAY, TURKEY - JANUARY 02: BOTAS' Floating Storage Regasification Unit (FSRU) ship, which is a ... [+]

LNG This Summer

Accounting for ~15% of global gas consumption, the 48 Bcf/d global liquefied natural gas (LNG) is on the move again.

After an obviously rough 2020, where Covid-19 caused just 1% demand growth, all-important Asian prices have been around $10 per MMBtu for summer, versus below $2.00 for last summer.

This could be the highest summer LNG prices since 2014.

Asia and Europe are both replenishing gas inventories after a harsh winter and colder April to ready for winter 2021-2022.

China’s May LNG imports, for instance, just set a record for the month, up 26% year-over-year.

This is great news for the U.S. LNG business, ranked as the third largest supplier.

U.S. gas has wide arbitrage opportunities since domestic prices are $3.00, even much lower for futures prices starting in Q2 2022.

Last year, it was a sunken export market that kept domestic U.S. gas prices at a crazy low $1.60 for June.

Beating Covid-19, U.S. gas demand last May-September was about the same as the records set for the same period in 2019, at ~75 Bcf/d.

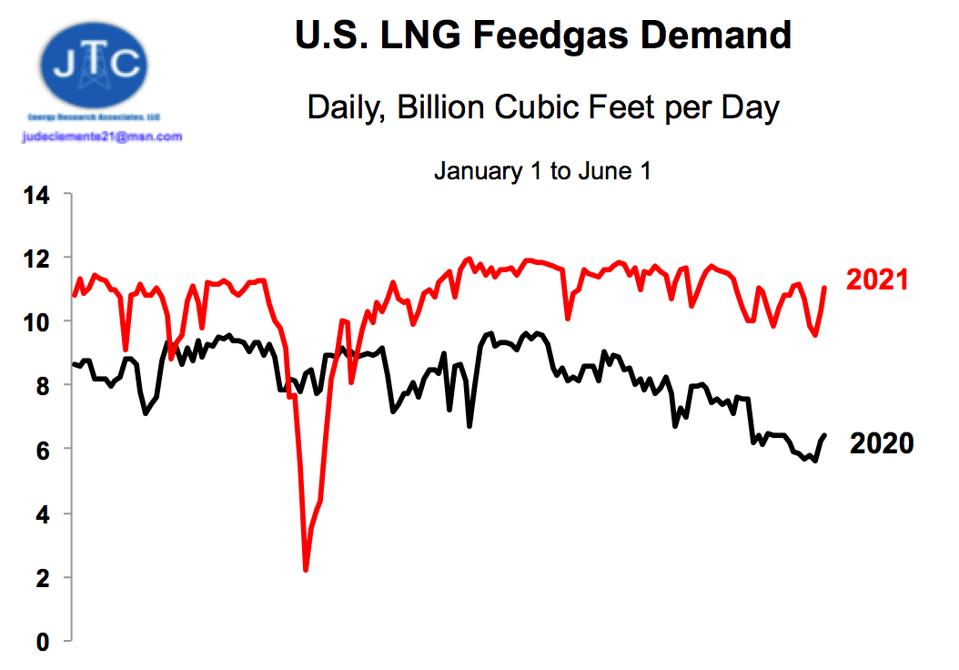

For April, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reports that our LNG exports averaged 9.2 Bcf/d, after setting a record in March at 10.5 Bcf/d.

Up from 6.5 Bcf/d in 2020, DOE has our exports at 9.0 Bcf/d this summer and averaging 9.2 Bcf/d for 2022.

Asia is the obvious price because it holds 75% of global LNG demand and is expected to account for a staggering 95% of new demand from 2020-2022.

U.S. LNG exports have been hitting record levels: Asian prices, for instance, are more than triple ... [+]

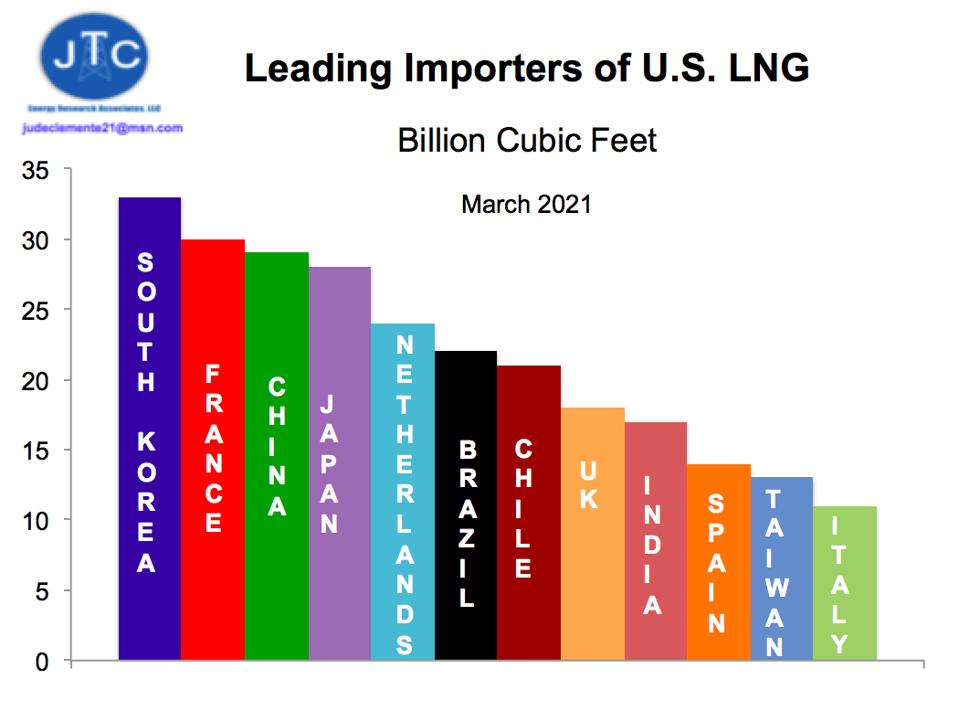

U.S. LNG has been reaching all corners of the globe, with South Korea and Japan normally taking the ... [+]

LNG Over the Long-Term

For natural gas as a commodity, global use will stay resilient even in a policy scenario where the human-induced rise in global temperatures is held to 2 degrees C or less.

This explains why net-zero carbon gas companies like BP and Shell are expanding their LNG portfolios, not to mention giant commodity traders like Vitol touting gas as a “cost effective and cleaner fuel solution.”

The reality is that progress towards a clean energy future must include investments in gas infrastructure: some 85% of all humans live in still developing countries, desperate for the very same energy that made us Westerners rich.

The notion that the still developing countries will somehow drastically curtail their energy options (i.e., block fossil fuel usage) is being overplayed by the developed countries.

Setting the example for others, gas now generates 40% of U.S. electricity, double second place coal and nuclear - a “dash to gas” that has significantly cut the country’s CO2 emissions.

In turn, the recent International Energy Agency’s advice – which contradicted its previous investment advice over the past decades – of no more upstream coal, gas, or oil projects is only being heard by its 38 member OECD countries.

These are the rich nations that comprise just 15% of the world’s population.

Simply put, Russia, China, and OPEC nations are ready to be gifted from such a recommendation, already helped by last week’s “climate activist wins” against Chevron, Shell, and Exxon.

Take OPEC’s Nigeria alone, where oil alone accounts for half of government revenues, which is ready to “Kick-start 100 Oil & Gas Projects Between 2021 and 2025.”

And be careful tossing climate shame at the Nigerian government for an obsession with economic development: 80 million Nigerians live on less than $1 a day.

As rich California painfully found out last summer, gas is the key backup fuel for wind and solar energy development because they are naturally intermittent, typically available only 25-40% of the time.

More long-term contract signings are reinstalling optimism for LNG developers.

The export industry is looking beyond the traditional Asian demand centers, like Japan, South Korea, and most recently the boom of China.

Along with currently Covid-19 devastated India, emerging markets such as Myanmar, Vietnam, and the Philippines are becoming vital for LNG sellers.

Demand in Southeast Asia could quintuple over the next decade.

With only one LNG project taken a final investment decision in 2020 (Sempra Energy’s project along Mexico’s west coast), new ones getting greenlighted will help facilitate growth in LNG consumption.

Fully developed Europe will remain integral as a swing demand center but incremental needs are limited.

The Middle East and Brazil will see moderate growth in LNG consumption.

Global LNG demand is slated to rise 40-50% over the next 10 years and perhaps even double to nearly 100 Bcf/d by the early-2040s.

There are currently around 16-18 Bcf/d of projects under construction, but an additional 8-10 Bcf/d of new projects will be needed over the next decade alone.

Longtime key suppliers such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Trinidad and Tobago, and the UAE are facing a declining ability to export.

The top five producers by 2030 will be Qatar, the U.S., Australia, Russia, and perhaps Mozambique and could total over 75% of LNG sales.

U.S. projects will need to be highly competitive to compete.

Developers here are also looking to enhance their ESG positioning with carbon capture and sequestration facilities at LNG plants, a key to reach Europe where U.S. LNG has already been denied because of methane emissions.

For example, EQT, the largest U.S. gas producer, has called to reverse the rollbacks of methane regulations.

Qatar’s $30 billion, 40% LNG capacity expansion project for its immense North Field (appraised at a mind-blowing 1,760 trillion cubic feet) is a game-changer and will equal 20% of global export capacity.

Qatar has the lowest production costs in the world and is looking to China for investments, a shift from Qatar’s normal partnering with the western majors for technology and global outreach.

Qatar is even working with ExxonMobil for the Golden Pass LNG export project in Texas.

Mighty Russia also wants to extend beyond its pipeline dominance to controlling 25% of the global LNG market over the next 15 years.

One more interesting question will be if Canada can eventually ship LNG from its western coast to Asia, having an advantage over U.S. suppliers in the Gulf that are more distant and must pass through the Panama Canal’s hefty tolls and traffic.

With huge offshore gas deposits but also facing violence and civil unrest, Mozambique is also LNG competition for the U.S.

But those of us demanding a much larger focus on alleviating horrific energy poverty (to me, the west has made it the world’s forgotten calamity) around the world have serious questions about Mozambique.

Only about 40% have Mozambique’s population has access to electricity, meaning that over 19 million people – about the population of metro New York City – in the much-hyped emerging LNG exporting nation have no access to electricity.

Yet, Mozambique is somehow primed to ship away huge amounts of natural gas, the world’s go-to fuel.

This has become a typical problem: 70-75% of the huge energy resources in sub-Saharan Africa, where some 600 million people have no access to electricity, has been bound for export to richer and mostly energy-fulfilled nations.

For an oil and gas industry critically looking to enhance its ESG positioning and public relations image, the Mozambique LNG export push must not become another black eye.

I reported on this very opportunity sometime back that “Oil And Natural Gas Companies Could Be Heroes In Africa.”

Even more, China is increasingly investing in sub-Saharan Africa for its plethora of minerals and critical materials required globally for “the green energy transition,” centered on hundreds of millions, if not billions, of wind and solar power farms and electric cars.

China’s Belt and Road cooperation to access natural resources around the world quietly just got its 45th partner: the DR Congo that mines over 70% of the world’s cobalt.

We do know that in our climate-energy discussion, distant promises come extremely cheap: “China burned over half the world’s coal last year, despite Xi Jinping’s net-zero pledge.

.”