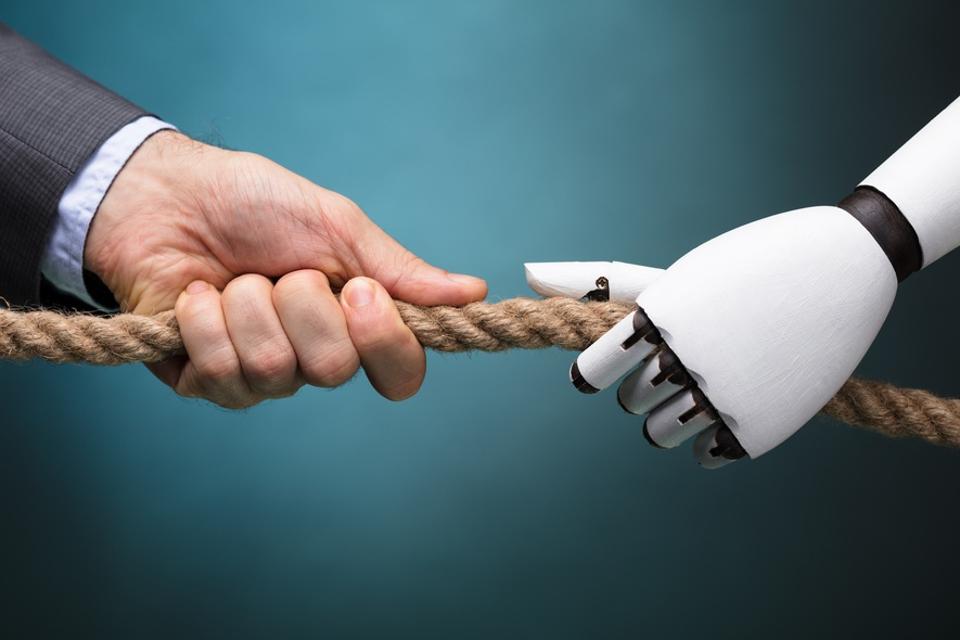

Getting Man And Machine To Collaborate Might Not Be As Easy As We Think

As artificial intelligence became more powerful, the discontent that it would eventually sweep all before it in the labor market grew and grew, with breathless reports predicting that up to half of jobs would be taken by our robotic overlords. Of course, that hasn't really happened, and more measured commentators now believe that AI is far more likely to augment jobs than eradicate them entirely.

New research from the University of Southern California illustrates how powerful this combination could be. The study explores how effectively humans and AI collaborate together, with a particular focus on the forecasting profession.

The authors highlight how collaboration between man and machine is increasingly common, especially in areas such as self-driving vehicles.

“The dialogue around [self-driving cars] acts as if it’s an all-or-nothing proposition,” they explain. “But we’ve slowly been acclimated to automation in cars for years with automatic transmissions, cruise control, anti-lock brakes, etc.”

Human-machine relationships

The team set up a forecasting experiment, known as Synergistic Anticipation of Geopolitical Events (or SAGE for short), which is where laypeople can work with AI-based tools to help them better predict the future. The laypeople were successfully able to predict, for instance, that North Korea would launch its missile test.

The SAGE-led collaboration is now being entered into the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency (IARPA) Hybrid Forecasting Competition (HFC) to properly put it to the test against some of the best forecasters around.

“SAGE aims to develop a system that leverages human and machine capabilities to improve upon the accuracy of either type on its own,” the researchers explain. “This Hybrid Forecasting Competition (HFC) provided a unique setting to study how people interact with computer models. [Other] studies typically involve one-off or short-term participation—the HFC recruited participants to provide forecasts for many months.”

The competition sees participants contribute to questions that are open for a number of weeks, with hundreds of participants competing against one another. Some of the participants were exposed to AI predictions, whereas others were not, with each participant free to choose whether to take the AI's suggestions on board or not.

Working well

Garry Kasparov famously suggested that men and machines working together are far more effective than either working alone, and is that what the researchers found? In fact, it was, with the AI-human teams beating both the expert forecasters and the AI forecasters quite comfortably.

“At the start of the HFC,” the researchers explain, “some of our teammates thought it was a foregone conclusion that the machine models would outperform the human forecasters—a hypothesis proven false.”

Nonetheless, the experience produced some interesting findings, not least of which was that human participants didn't use the statistical models a great deal, which the researchers believe resembles how we so often tend to ignore advice from other humans as well.

“We expected many instances where forecasters over-relied on the models," they continue. "Instead, we found people over-relied on their personal information. Forecasters readily dismissed the model prediction when it disagreed with their pre-existing beliefs (known as confirmation bias).”

A hard sell

Interestingly, people still seemed reluctant to listen to their AI advisors, even when they were explicitly told that doing so would be very helpful to their cause. So while the use of AI did improve outcomes, it shouldn't be taken as an easy sell or a fait accompli that improvements will emerge.

“Overall, the addition of statistical models into a forecasting system did improve accuracy,” the researchers say. “However, it shouldn’t be a foregone conclusion that humans will use the tools well or at all.”

This has obvious implications for the way that we integrate AI-based tools into our workplaces. The results remind us that it's not enough to "simply" develop a tool that does its job very well if it's not easy to actually convince people to team up with it. It's no good having a satnav system advising us on the best route if we always ignore its suggestions.

For man and machine to work well together will require a high level of trust that the machine can be relied upon. In this way, it's not that different from nascent human relationships, where we often require a degree of experience before we fully trust people and their capabilities.

It's a finding that the researchers believe has significant implications, both for the engineers that design AI-based tools, and for the end-users who are ultimately tasked with collaborating with them.

“The average person should learn to be more deliberate in how they interact with new technology,” they conclude. “The better forecasters in our study were able to determine when to trust the model and when to trust their own research—the average forecaster was not.”