Today, the global internet shook for about an hour. Due it seems to technical problems at an “edge cloud” company named Fastly, websites including those for the New York Times, CNN, and the UK’s government failed. The lessons from this event are IT-related, of course, but they also extend beyond into how businesses should plan their futures.

We live in an age of ever more rapid, and more consequential, discontinuities. Whether it’s a pandemic, cyberattack, or natural disaster affecting supply chains, events transpire which upend carefully orchestrated systems built on a presumption of predictable, linear change. I first learned this lesson back in 1999, when I was responsible for one of the world’s first mobile internet devices, sold by Ericsson. It was selling super-fast, until an earthquake in Taiwan disabled the single plant making a critical component for our touchscreen supplier. I had never even heard of the company affected. But I realized then that I should have known about these systems. Today it seems that metaphorical earthquakes are not flukes but routine events.

This means that businesses need to plan for discontinuities, and not just in the sense of risk-mitigation. These events also create opportunities. Consider how the pandemic became a growth bonanza for many tech firms.

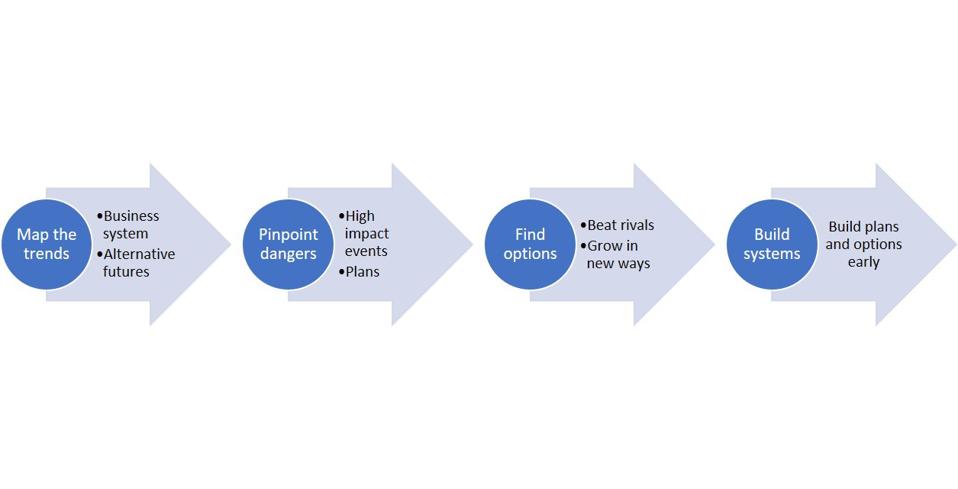

What concrete steps can you take? I’ll be writing about these themes extensively in future pieces, but start with these four implications:

Take these four steps to prepare for rapid-fire discontinuities.

1. Map the trends impacting your business system: Most companies look at their immediate industry dynamics, but think more broadly about factors such as inter-connectedness of companies, hard-to-replicate specialist firms, substitutes for your products or services, and new ways your outputs might be used. Don’t just look at your business system as it is today, but consider where it might be in three years. Plot alternative views of the future so you don’t just settle on one consensus perspective, which typically will look very much like the world as it is today.

2. Pinpoint the dangers: Resilient businesses avoid relying on one set of suppliers, or one set of assumptions about how the world will operate. They consider what might seem like small probability events which could have an outsized impact if they do transpire. Don’t just list them out, like a public company is required to do in its annual report filed with the SEC. Consider your mitigation plans.

3. Find options in the opportunities: Change creates new openings for growth. How can you position your business to benefit when events swamp competitors, or generate new customer needs or even new customer types? Chart out how these opportunities link to vulnerabilities and the nodes of your business system. Push to think about the potential silver lining for your firm in every major change that could affect that ecosystem.

4. Create systems to manage rapid change: Some events – like a global internet outage – are obvious and call for rapid firefighting by affected companies. But others are more subtle yet equally impactful, like the eventual effects of the plummeting birthrate in advanced economies during the pandemic. They cannot all be managed from the C-suite. Rather, you need people in the middle of the organization with the systems and incentives to continually spot change and develop growth options in response. A little energy and funding spent early toward mitigating risks and building growth options can go a very long way to getting your firm ahead of competitors when the effects of these changes become obvious to all.

Today’s headline is about a global internet outage, and tomorrow’s might be utterly different. But the certainties behind the varying headlines are that 1) change is accelerating, 2) what used to seem long-tail risks are transpiring with more regularity, and 3) the impacts on one part of the economy quickly ricochet to others. Preparing now will help you avoid going dark in the future.