Man stocks up on toilet paper as Canadians purchase food and essential items in Markham, Ontario, ... [+]

The reduction in the U3 unemployment rate (Household Survey) from 6.1% to 5.8% looks like good news, as does the Payroll job growth number for May of 559K (Payroll Survey). But, while the new job growth number is better than April, it still didn’t meet market expectations. As a result, at week’s end, interest rates retreated as markets now discounted a longer period before the Fed begins to tighten policy (i.e., “taper” their $120 billion/month QE purchases).

Here is some perspective:

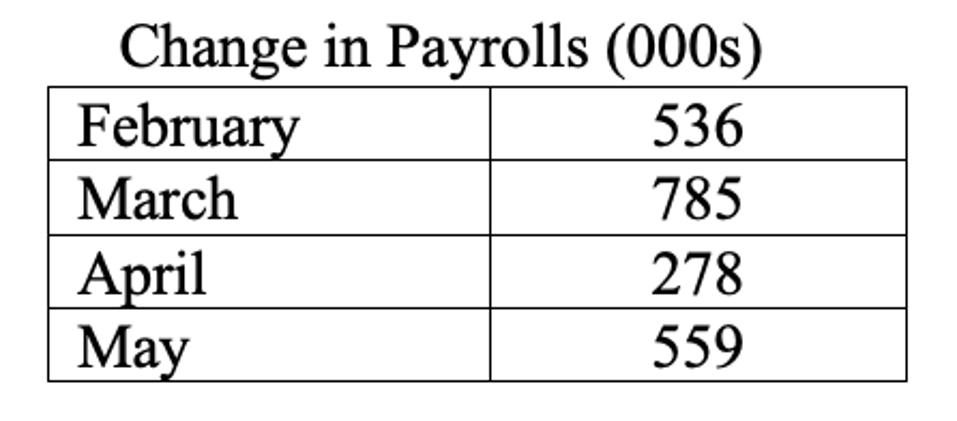

- Just two months ago, there was a widely held belief in the financial community that the economy would experience several months of payroll growth in excess of one million. The table shows the data from February through May.

Change in Payrolls (000s)

The mean of these four months is 539.5K. A month ago, April’s 278K was widely thought to be an aberration (not by us!). (March’s initial reported payroll number was >1 million.) Now it looks like both March and April were aberrations, one offsetting the other. And it looks like 500K-600K is what we can expect in payroll growth, at least while the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program ($300 weekly unemployment supplement) continues to dis-incent a return to work (more on this below).

- The U3 unemployment rate fell to 5.8% from 6.1% and U6 to 10.2% from 10.4%. Almost all this was due to a fall in the labor force itself, as the Labor Force Participation rate declined. Declines are normally associated with weak, not strong, job markets.

- The Household Survey (taken at the same time as the Payroll Survey) corroborated the Payroll Survey showing job growth of +444K. However, 353K holders of those newly created 444K jobs (i.e. 79.5%) were “multiple job holders,” meaning, only 91K came from the ranks of the unemployed. That partially explains why the weekly data are barely moving.

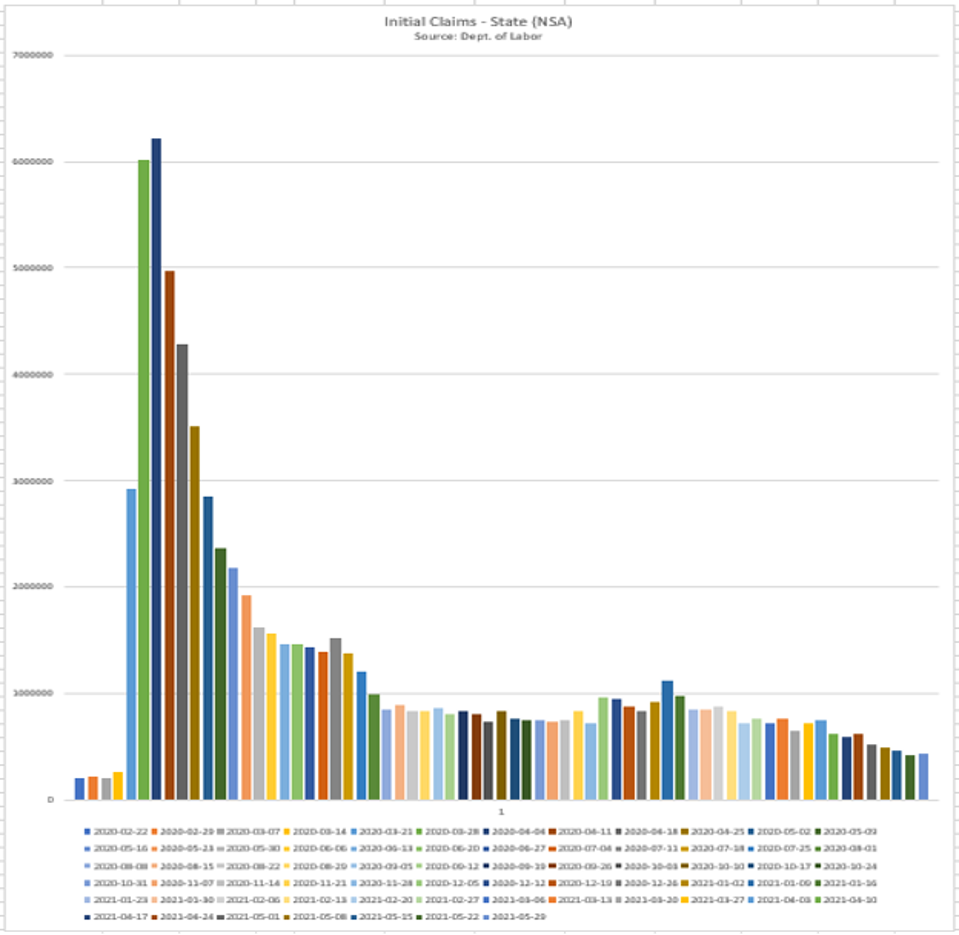

- Markets cheered the Thursday (June 3) release of state Initial Unemployment Claims (ICs) as the headline number of +385K breached the 400K level for the first time since March 2020. Unfortunately, 385K is the Seasonally Adjusted number, and the pandemic, shutdowns, vaccines, and re-openings are anything but seasonal. The more reliable Not Seasonally Adjusted data increased from +419K (week of May 22) to +425K (week of May 27). Not a lot, but the wrong direction, especially in the face of vaccines and re-openings. We will also remind our readers that these are ICs (new layoffs), still running more than twice as high as the pre-pandemic “normal.” How can this happen in a “boom” economy? (We answer that question in the section entitled “The Boom” below.)

Initial Claims- State (NSA)

- On the positive side, there was a significant fall-off in the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) IC program (for self-employed and gig workers). For the May 29 week, this number fell from +95K to +76K. It was as high as +452K the week of April 3. We don’t think it will go too much lower until the program ends on September 6 (at which time it will fall to 0).

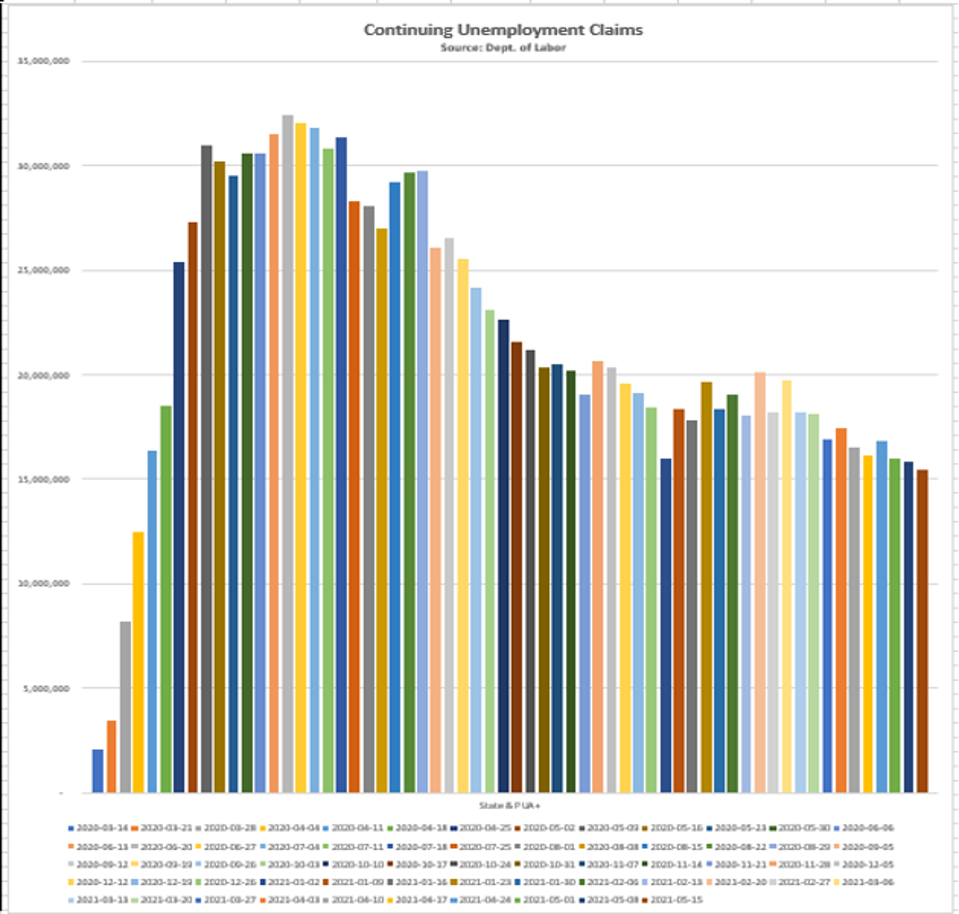

- The biggest concern continues to be the snail’s pace of decline in Continuing Unemployment Claims (CCs) which barely fell (to +15.4 million the week of May 29 from +15.8 million the week of May 22).

Continuing Unemployment Claims

- We have written in these blogs that we believe that the $300/week federal supplemental payments have been a significant disincentive for a return to work in the lower wage industries. We now have 24 states, which, according to Morgan Stanley

MS , represent 29.3% of all unemployment recipients, that will end the federal supplements between June 12 and July 19. Using the time series data for each state, we will be able to determine if unemployment falls more rapidly in those states than in the states that continue to disburse the federal $300 weekly supplement. If they do, as we suspect, that will be a strong indication that the supplement has been the major culprit in the unemployment saga. Stay tuned!

Inflation

Average hourly earnings popped +0.5% in May, much higher than expected. That’s a 6.2% annual growth rate, and it caused a stir among those believing that “systemic” inflation is emerging. Even some Fed governors remarked that a continuation of such trends may cause the Fed to act sooner to tighten (taper) than they have been indicating. However, after dissecting the data, here is what we see:

- Leisure/Hospitality: +1.2% (May); +2.8% (April)

- All remaining sectors: +0.3% (May)

Leisure/Hospitality was the pandemic’s most seriously impaired sector; such a result during the biggest re-opening month so far (June may be even bigger) should not be surprising. On a Y/Y basis, wage growth is just +2.0%, while labor productivity has grown (5.4% in Q1 and 4.1% Y/Y). As long as productivity growth is the same or greater than wage growth, there can be little in the way of “systemic” inflation.

The “Boom”

In a piece called “What Hoarding Toilet Paper Means For Economic Data” (5/30/21) (Bloomberg), authors Alloway and Kennedy discuss how the hoarding of toilet paper (TP) early in the pandemic “has now gone global, in the sense that more and more companies are buying essential materials [in excess of their pre-pandemic needs] in order to manage potential future supply shocks.” In every survey we’ve seen of late:

- Prices paid have risen significantly

- Delivery times have greatly lengthened

- Order levels are up

- Backlogs are up

- Labor is scarce

Let’s think about this from a macroeconomic perspective. This appears to be a one time and temporary change in desired inventory levels, not by one company, but by whole industry sectors. Pre-pandemic, many of these companies had “just-in-time” inventory policies, which kept inventories at minimum levels, as the supply chain operated efficiently to get them required inventory when needed, rather than via a company owned stockpile. But now, as a result of supply chain issues caused by the pandemic, many companies have decided to hold much higher inventory levels.

Assuming that the post-pandemic demand for a company’s product is similar to its pre-pandemic demand, then, once the new/higher level of desired inventory is achieved, replacement orders for inventory will return to the pre-pandemic levels from the bloated order levels today needed to rapidly achieve the higher desired stockpiles. That is, those higher levels of inventory, given pre-pandemic final demand, will be achieved at pre-pandemic inventory order levels.

The conclusion is that today’s sky-high levels of demand (the “boom”) and resulting supply shortages are temporary, as are the price spikes associated with such shortages. Early in the pandemic, at the consumer level, we saw the prices of TP and hand sanitizer spike. Today, TP prices are near pre-pandemic levels, and most stores can’t get rid of hand sanitizer at any price!

So, when will such price spikes end and inflation retreat to its pre-pandemic trend? That’s not a question that has any recent historical precedent. Some raw materials come from emerging market countries, still hard hit by the virus. So, a return to pre-pandemic inflation rates may take longer than a few months. Nevertheless, we should begin to see supply chains ease by late in the year. The survey data from the regional Fed banks, from the University of Michigan, and from the Conference Board, as well as others, will serve as leading indicators of a return to some semblance of a pre-pandemic “normal” in the supply chains.

Conclusions

The unemployment data continue to disappoint. However, we believe the data and labor markets will begin to improve once the federal supplemental payments cease – soon for 24 states, and after September 6 for all states.

Despite higher-than-expected wage data, most of the outsized wage gains were in the low wage Leisure/Hospitality sector, the sector hardest hit by the shutdowns. That sector is now re-opening in the face of dis-incenting unemployment benefits. No wonder wages are rising! But we don’t see the same issue in the much of the rest of the economic sectors.

The hoarding of TP at the retail level early in the pandemic has now spread to wholesale, retail, and manufacturing sectors that need physical inventories. To protect against future shocks, desired inventory levels have risen, and, due to supply chain issues, “shortages” are rampant. Delays and rising prices result as does double (triple?) ordering. However, because post-pandemic demand is going to be similar to pre-pandemic demand, those delays and price spikes will prove to be temporary, even if desired inventory levels remain high.

(Joshua Barone contributed to this blog)