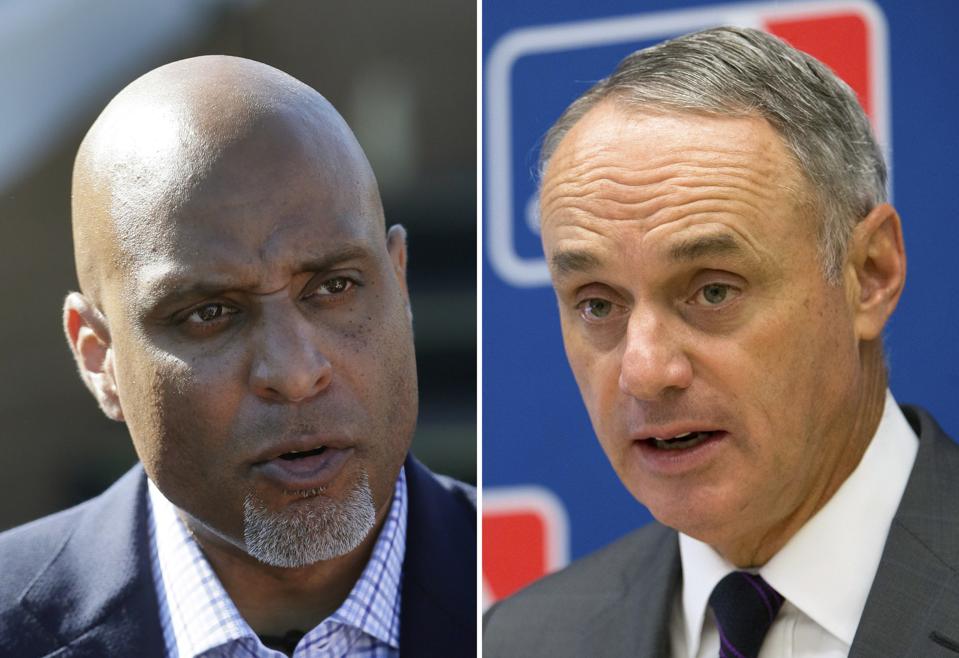

Major League Baseball Players Association executive director Tony Clark (l.) and baseball ... [+]

The march toward December 1, when the current collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between Major League Baseball and the Players Association expires, has already been fraught with tension between the two sides, with baseball pundits predicting an ugly showdown, and possibly, the sport’s first work stoppage since the crippling 1994-95 strike.

The players’ union fired the latest salvo in the ongoing cold war: a grievance filed against the league, in which the players are seeking a reported $500 million in damages.

According to a New York Post report earlier this month, the union contends that MLB acted in bad faith last year when determining how many games should be played for the truncated 2020 season. The report listed the $500 million amount as the equivalent to the pay players would have received if 20 to 25 additional games were played in 2020.

The players and ownership feuded over money and salary payout in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic last year, and ultimately the season commenced when baseball commissioner Rob Manfred authorized a truncated, 60-game regular season. The two sides couldn’t come to an agreement after several proposals were on the table.

A Players Association spokesman confirmed that a grievance has been filed, but did not comment further. Two separate baseball sources confirmed MLB has filed a counter grievance.

Besides further stoking the animosity between the two sides, does the union’s grievance have any legs? According to numerous sources connected to baseball, the players appear to be the underdog in this latest round, and historically, the union and its members have been on the losing side of grievances more often than not. According to multiple sources, MLB has requested that the union expedite this latest grievance, but it’s possible the matter could drag on until after the 2021 season concludes, and further complicate CBA negotiations.

In any grievance, there is one representative each from the union and MLB, and a third-party neutral arbitrator — currently Martin Scheinman — who casts the pivotal decision. Both MLB and the union can terminate an arbitrator at any time. In 2012, for example, MLB fired arbitrator Shyam Das, after Das overturned Milwaukee Brewers outfielder Ryan Braun’s 50-game doping suspension. (Braun eventually would serve a 65-game suspension in 2013 for his ties to the Biogenesis scandal).

“It’s very early in the process,” one source said of the current labor talks. “The union filed the grievance to create some leverage in negotiations. Whether or not that proves to be the case, only time will tell.”

Baseball is likely pushing for a quick resolution to the grievance since a half-billion dollar liability hangs in the balance. There is also the prospect that the league could be in a very different economic position come December 1. In an interview earlier this year, economist and Forbes contributor Andrew Zimbalist said that in addition to the massive losses the 30 MLB teams sustained in 2020 — with no fans in attendance at games — “there are going to be ongoing losses this year,” despite the return of fans and teams earning gate revenue again.

Before the 2021 season began, one baseball executive said that the labor situation would be a “distraction” for the entire year. “The unwillingness of the union to even talk about some of the issues is alarming," said the executive. But the union grievance notwithstanding, the labor storyline has mostly remained in the background as the sport navigates a full season while the pandemic is still ongoing. The unusual amount of no-hitters thrown this early in the season (six), and stars like Fernando Tatis Jr. and Shohei Ohtani are drawing fans’ attention as opposed to contentious labor issues.

One league source called the union’s grievance “a waste of time,” while another baseball insider said the union has “a high hill to climb” in this latest battle with ownership. In March 2020, the two sides reached an agreement on issues such as player service time and salaries in advance of whether or not any games would be played amid a global health crisis. But the March 26 agreement also gave Manfred the authority to implement a schedule of whatever length, which he exercised.

While one agent said the grievance is “legit” and that there could have been more than 60 games played last year, is this latest strategy by the union’s executive director Tony Clark and its members nothing more than a Hail Mary? Even if Scheinman, the arbitrator, were to rule in the union’s favor, the damages awarded might benefit veteran players more, especially those at the end of their careers.

For the younger stars, the more complicated labor battle still looms.